Klimt and the Depiction of the Cycle of Life

1903-1915

In addition to representational portraits of women from Viennese society and innovative landscape paintings featuring imagery from the region around Lake Attersee, Gustav Klimt’s oeuvre also includes numerous allegories dealing in particular with depictions of the circle of life. At least since the faculty paintings, especially in “Medicine,” Gustav Klimt moved away from traditional allegories, which, until then, he had integrated into his public decorating commissions. The metaphysical symbol came to the fore.

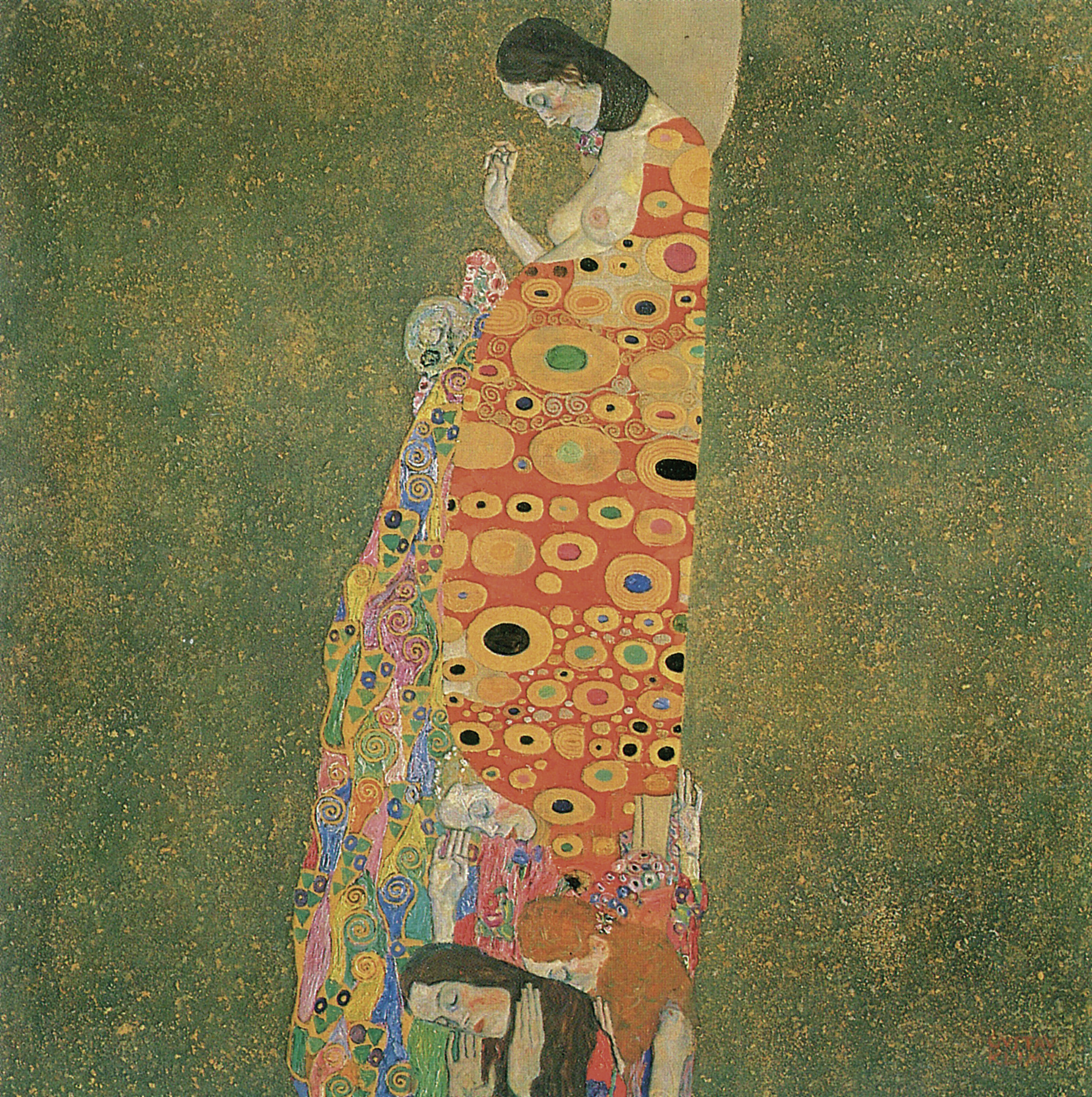

During the Internationale Kunstschau exhibition of 1909, Klimt presented his two paintings “Hope I,” from 1903/04, and “Hope II,” from 1907/08. Both works deal with the development of life. While the nude, pregnant woman in “Hope I” is facing the spectator with open eyes, the female figure in “Hope II,“ also pregnant, is wearing a dress with ornamental patterns and has her head lowered toward the ground. In both paintings, death is a symbolic guest. This is very different from the artist’s biggest easel painting (180 x 180 cm) “The Three Ages” from 1905, in which the three ages of childhood, youth, and old age are represented by three female figures. Here also, death is omnipresent—not as a skeleton or skull, but as a black beam in the top part of the painting and as a veil, wound around the feet of the young woman and the child.

The picture was exhibited in 1911 at the International Exhibition of Art in Rome, where it won the “Gold Medal” and was purchased by the Galleria Nazionale d´Arte Moderna.

His monumental allegory “Death and Life” was also exhibited, in a preliminary state, in Rome in 1911, when it had only recently been completed. This work is also a depiction of the cycle of life, symbolized by a bundle of humans of all ages on the right half of the painting, and death, wrapped up in a blue cloak, on the left. In this first state of Klimt’s painting, the figure of death has his head lowered and seems somewhat stiff. In the reworked state after 1915, however, he appears more active, holding a red club in his hand and fixating the group of people facing him with his glance. With their eyes closed, the group seems suspended in a dream state; only the female figure directly in front of death is keeping her big, empty eyes open. Today, we can only guess what made Klimt decide to the change the first state. The First World War and the resulting omnipresence of death, as well as the death of Klimt’s mother in 1915, might have contributed to his decision. In 1916, the painting was exhibited in the Berlin Secession under the title “Death and Love.” Today, it can be admired in the Leopold Museum in Vienna.