Alfred Preis

Planning the MemorialAs early as 1942, the Hawai‘i Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) initiated discussions about a fitting memorial for World War II. Two schools of thought emerged: the first, articulated by Jim Morrison, favored the development of a living memorial which would serve a socially useful, practical purpose, such as the War Memorial Natatorium which honored Hawaii’s World War I dead. The second viewpoint, maintained by Preis, supported the concept of an evocative memorial whose form would provoke thought and arouse feelings. In the midst of war, such concepts were merely discussion points, and it would not be until 1949 that Hawaii’s Territorial Legislature established a Pacific War Memorial Commission (PWMC). The Commission turned to the Hawai‘i Chapter of the AIA for assistance. Serendipitously, Preis was secretary-treasurer of the chapter in 1949, vice president in 1950, and in the following year was the chapter president. Under Preis’s guidance the AIA set forth a plan for a series of six memorials between Punchbowl crater and Red Hill, and Preis became the AIA’s point of contact with the PWMC, as well as chair of the design team for one of the six memorials, the one for the USS Arizona.

In the years immediately following the war, the Navy deemed the recovery of bodies from the wreckage as too dangerous, and so did little toward the preservation of the sunken ship. It was the head of the Pacific War Memorial Commission, H. Tucker Gratz, who spearheaded the effort. Because of Gratz’s consistent pleas, a lonely flagstaff was erected over the site five years after the war’s end. Eventually, in 1950, a temporary platform over the main deck was constructed with a plaque and an obelisk, and it was accessible by boat. But by the late 1950s, approximately 100,000 people per year were visiting this makeshift site.

The design team recommended by the A.I.A. for the Arizona memorial, which included Preis, Tom Perkins, Allen Johnson and Clifford Young, was accepted by the Navy. Young wished to prepare his own design, while Preis, Johnson and Perkins worked in conjunction with each other, and were ultimately selected to design the memorial.

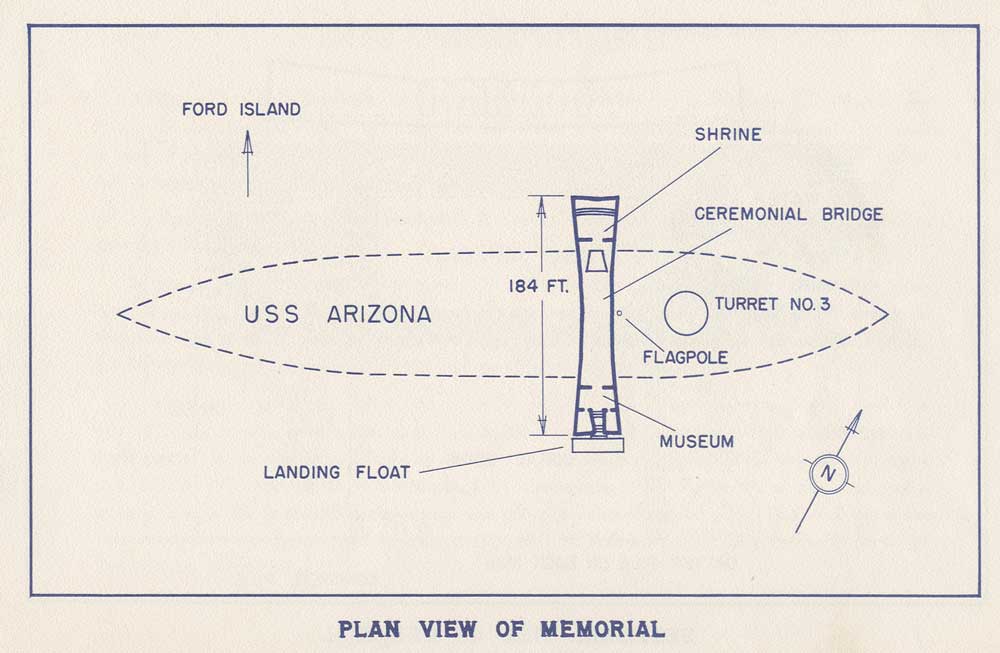

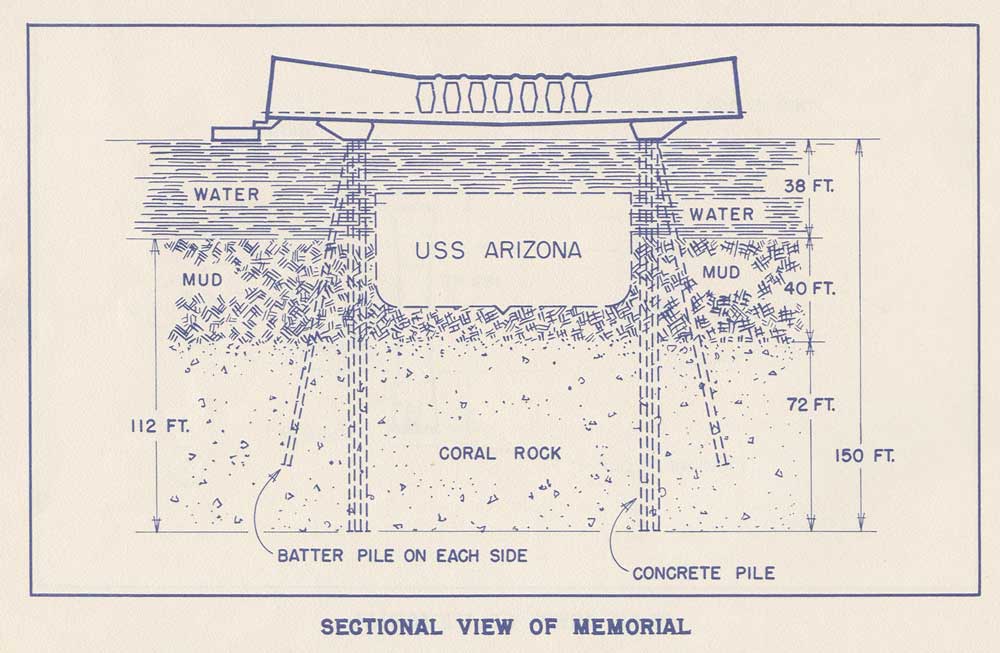

The Navy’s program for the design of the memorial stipulated the inclusion of a bridge which was to straddle, but not touch the sunken Arizona. Johnson & Perkins worked on a plan for a single reinforced concrete slab over the ship with a pavilion in the middle, while Preis worked on an alternative plan for an underwater room accessed by stairs from Ford Island, allowing visitors to view the hull of the Arizona through portholes. This initial concept, however, was deemed far too macabre. Preis subsequently reconceptualized the form as an above-water structure reached by boat, similar to the already existing platform, but as a real piece of architecture. Preis’s new concept, a 158-foot long form over the battleship, was ultimately the right, sensitive design move.

About two weeks prior to the presentation of the design to the Navy and the PWMC, engineer Alfred Yee informed the architects that their concrete slab as bridge design was well beyond the budget. Working with Yee, Preis developed a new, cost-effective, bridge design, which cantilevered the two ends of the bridge and used a catenary curve to support the middle. To reduce the weight, holes perforated the structure’s mid-section. From these engineering requisites, emerged the final, current design of the memorial.