Alfred Preis

A Public Icon: From a Master of Hawaiian Modernism to Hawaii’s ‘Art Czar’In an article published sometime before the end of World War II, Alfred Preis reflected on postwar homes by envisioning a new form of architecture – individual in design and removed from the principles of both traditionalism and international modernism. Following the strong Vienna Secession era sentiment, “To every age its art, to every art its freedom,” Preis wrote that “to lift architecture into the realm of art it must interpret the spirit of the times.”

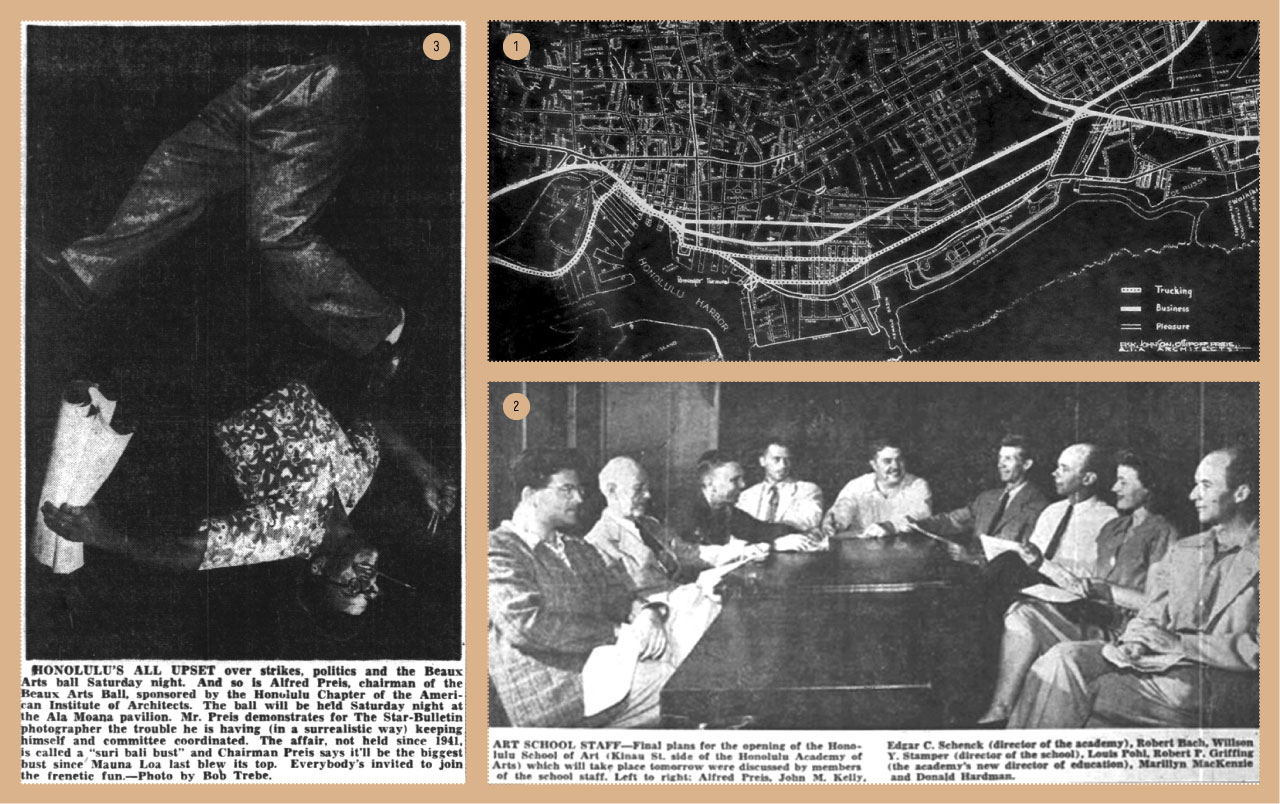

Toward these ends, he had helped to envision a master plan for Honolulu, Future Honolulu, that attempted to preserve its natural beauty, while also recreating Hawai‘i as a center of communication and administration in the 1940s. The authors of the master plan, Associated Architects, including Philip Fisk, Allen Johnson, James Morrison, Vladimir Ossipoff, and Alfred Preis, envisioned a “‘Pacific’ Memorial for exposition, festivals and a Forum to aid in the development and exchange of ideas pertaining to peaceful, human relations and to make these the subject of scientific inquiry.”

This master plan evidenced many of Preis’s personal visions that had emerged after his arrival and his short internment as a suspected enemy alien after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His ideas bore some resemblance to his Keehi Lagoon airport proposal (1943) with the Hawai‘i architect Hart Wood. Some of his concepts can also be traced back to Preis’s time in Vienna, ranging from the sweeping urban planning strategies of arterial and one-way traffic routing in Otto Wagner’s urban plans for Vienna to expatriate Fritz Malcher’s ground-breaking steady-flow traffic system adopted in the US design of freeways. In addition, the masterplan also incorporated ideas from the planning of the nineteenth century Ringstrasse as a main cultural artery for the city, as well as rationalized planning methods promoted by the European International Congresses of Modern Architecture (CIAM), which promoted the organizing of cities according to areas of use and function.

These examples of social and urban planning captivated Preis’s creative mind – first as an architect – and later as a public advocate.

After being interned for approximately four months at the Sand Island Detention camp, the Preises were released. For much of the war’s duration, Preis worked for his release sponsor, Chester Clarke – who he designed a house for during his Dahl & Conrad years – as an efficiency engineer and architect for Clarke-Halawa Rock Company, a quarry contractor. During this time, he began to develop his advocacy for two major areas that would become a foundation of his later life and career. The first was the interest in the preservation and treatment of Hawaii’s pristine and fragile natural beauty. The second was his strong interest in the fields of arts and music – these were lifelong passions that eventually turned into a second career. He began to transpose and translate his Viennese, humanistic social-liberal upbringing through the general environmental and social climate of Hawai‘i: Instead of working on a more typical client-by-client basis, Preis considered his ultimate clients to be the local population as a whole.

Through the 1940s, he formed close and significant relationships with other modern-minded architects, leading to the formation of Associated Architects, a rather unusually structured assembly of competing architects that nevertheless shared common interests. First through private get-togethers at Preis’s home, Associated Architects grew into an influential group working and consulting with government and military on architectural matters for the Territory. Associated Architects worked through a system of internal competition – each architect would submit his own project plans – and then the group would select the best design or a combination of various elements of the favored designs for the final lead project architect. Several of the projects that were developed through this system of internal competition setting resulted in some of Hawaii’s most progressive buildings and developments of the 1940s and early 1950s, including not only the Future Honolulu master plan, but also the University of Hawai‘i Administration Building, veterans’ housing projects, and the Laupāhoehoe School, among many others.

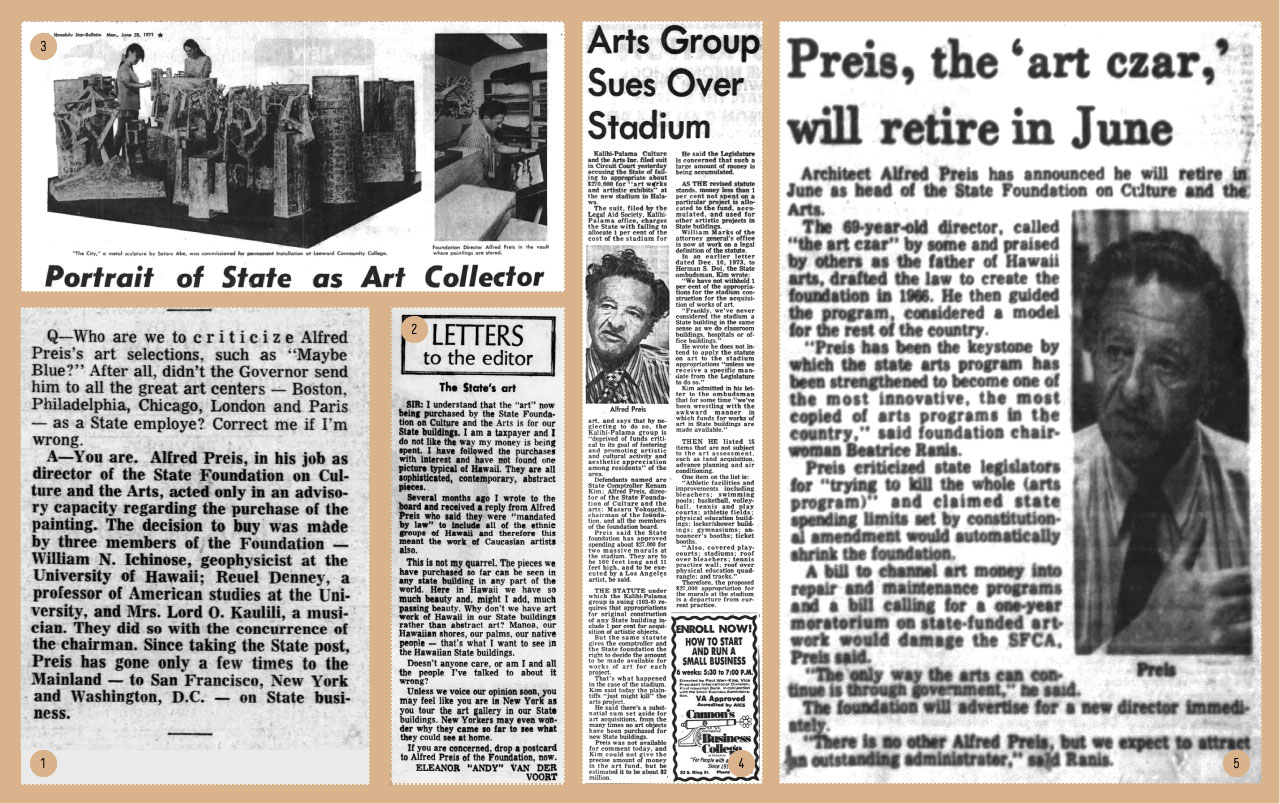

As early as 1946, Alfred Preis served as a staff member of the Honolulu’s Art School. This position granted him not only authority over a subject dear to him but also a venue for various publications and exhibitions. It was only one of many community service positions he held over his career, which spanned from an enthusiastic involvement with the local symphony orchestra to public Parent Teacher Association groups – Preis felt community engagement was critical to have his positions publicly heard. For example, the local Honolulu Art Society, of which he was board member, prepared the Modern Home exhibition in 1947.

It featured the work of Preis and many of his design colleagues as they attempted to envision the new modern home and society of Hawai‘i. Newspaper reports also indicated the strong support and advocacy of his wife, Janina.

Issues of domestic design were the subject of a 1953 panel discussion titled “Family Living – The Hawaiian Style” and involved Alfred Preis, now an established architect and an active member of the community. Even while his career as local architect flourished, he still steadily increased activities in professional, and community societies such as the American Institute of Architects (AIA), the World Brotherhood Organization, and the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra.

He generated a consistent presence in local newspapers, documenting his passion for arts (especially the local symphony), along with the preservation of the local environment through urban planning. Among the topics he advocated were the development of Diamond Head as an international arts forum, of Waikiki Beach, and the possible funding and relocating of a symphony – projects that never materialized. Other advocacies included his strong proposition for a modern state capitol and various discussions on its location.

Between 1961-1967, serving on the Chamber of Commerce Beautification Executive Committee Preis not only got a taste of the bureaucratic procedures but also of the mechanics in advocacy such as the development of the Pali lookout or a greenbelt through Honolulu. Finding himself transitioning from a celebrated architect of mainly residential work, Preis embraced his newly found avenues of public engagement. During his time at the chamber of Commerce he chaired The Diamond Head planning committee. As State Planning Coordinator, a position bestowed onto him through an acquaintance of Hawaii’s then Governor Burns, and a position he held between 1963-1967, Preis finally found his opportunity to introduce ideas concerning environment and planning into legislation.

He was privy to various agendas from the mainland, while his main objective remained to advise the governor “on social and aesthetic planning questions.” One such agenda coming from mainland US was the formation of a national organization of the arts, which ultimately led to Preis’s bill that formed the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts (HSFCA) in 1965. Hawai’i was the first US State to feature such an institution. Following his termination as State Planning Coordinator, Preis assumed the position of Executive Director of the HSFCA, acting often as the sole judge and critic and purchaser of art. This caused some controversies: Critics engaged with Preis over his choices of patronage in art, which, in his uncontested position, had resulted in over 2000 purchased artworks by local, national, and international artists and also lent him the moniker, “art czar.”

All the while, Preis pursued the development of an emerging arts scene, attempting to find meaningful activity, not only for the predominantly white elite, but for all people, regardless of ethnicity and income level. This novel approach suited this young, progressive state that often promoted inclusivity and generosity to make art a foremost educational medium on a state level. His involvement can be further credited with extending the sponsorship of artists from mainly privately funded contexts to a nationally funded endeavor. For example, the Artists in the Schools Program, which he established in 1970, provided opportunities for local students from kindergarten through 12th grade to work with professional artists.

Critics, however, latched onto the expense and the pseudo-dictatorial drive that had forced the legislature to set aside one percent of the state building budget towards the purchase of public art. Among those were politicians, newspapers, and powerful lobbyists. In 1976, things came to a head with an audit that exposed obscure accounting procedures, laying bare the fact that Preis was the sole decision maker in the commissioning and purchasing or art in the State of Hawai‘i. All of his work came to an end with his announcement of retirement in 1980 at the age of 69, following a prolonged fight with legislature and critics who sought to undermine the very foundation he helped to shape.

In retirement, Preis’s public engagements shifted to a broader support of artists in school programs, creating the Alliance for Arts in Education. After a brief visit to Vienna in 1980 – the first since his escape – and a further two years of engagement in the Alliance, Preis finally retired from all public activities. With ailing health, he maintained a diminished presence and advocacy appearing only in several dignitary events. He passed away on March 29, 1994 in his chosen home of Hawai‘i.