Alfred Preis

Formative years in Vienna and escape from the Nazis (1911-1939)Alfred Preis’s Vienna

Alfred Preis was born in Vienna on February 2, 1911 to a working class, Jewish family. His mother, Hermine Heim (1884–1942) was from Sopron, Hungary and his father, Ignaz Preis (1880 –1941), was Viennese. The couple married in 1910. Alfred, their first son, was born about one year later.

Shortly after his father joined Austria’s military forces at the outbreak of World War I, Alfred contracted tuberculosis at the age of four. His mother managed to have Alfred sent to recover at a sanatorium near the Alps. The sanatorium not only saved his life, but his experiences there changed his outlook. Most of the other patients were from middle and upper class families. The nurses spoke in crisp High German to him, as opposed to the Viennese dialects he was accustomed to. Observing his innate intelligence, his nurses read to him frequently. At an impressionable age, his time at the sanatorium opened for him a whole new world of literature and the arts.

After he recovered, the Preis family moved into a rambling old building at Wiedner Hauptstrasse in Vienna’s fourth district, just a few blocks from Karlsplatz and the Vienna Ringstrasse. Preis estimated that it was a roughly 400-year old, two-story structure – now demolished. Originally designed as a cavalry fortress around the time of the Turkish siege of Vienna in the sixteenth century, it had been converted into apartments in order to meet the critical demand for housing after the war. Its large rooms and ample courtyards had been ravaged by time. Crowded, freezing cold in the winter, and infested with bedbugs and rats, it also was, in Preis’s own words, full of “people very different from those in my sanatorium.” But it was located in an extraordinary location for a curious young boy. He was enveloped in the richness of Vienna’s cosmopolitan culture near the famed Ringstrasse.

The “Ring,” as it was known, was a visionary act of nineteenth-century urban planning, rivaling – if not surpassing – Baron von Haussmann’s contemporaneous redesign of Paris. The Empire’s Parliament, the city’s Rathaus, the Burgtheater, the University, a public garden, and museums, among other impressive structures were designed by the city’s most prominent nineteenth century architects in imperious styles that ranged from the Greek to the Gothic Revival, and the neo-Baroque. These monuments to a purportedly more democratic Vienna under a benevolent monarchy were interspersed with dignified upper-middle and upper-class homes built through the end of the nineteenth century. In this environment, Preis found himself in the midst of city’s most storied and progressive examples of nineteenth and twentieth architecture.

Preis, with his native intellect, reported feeling distinctly different from his neighbors. Although almost everyone around him spoke the local Viennese dialect, he revolted by speaking only in High German. Preis spent as much time away from his apartment as he could. When not in school, he went to the nearby art museums and explored his neighborhood architecture. Every Saturday he attended the affordable afternoon performances at the Burgtheater and the Volkstheater. The Vienna Opera House was also just a ten minute walk from Preis’s apartment.

Through the 1920s, Preis nurtured his all-consuming love of the opera. During this crucial time in European progressive theatrical design, Preis would have been a firsthand witness to the ways that architects and stage designers re-envisioned theater architecture and scenic design. He became a member of the State Opera claque, helping to lead applause at performances. He was able to travel around Europe with the opera company. Captivated by these experiences, Preis enrolled in acting school and considered becoming a scenic designer after graduation.

Theater was not his sole source of creative inspiration. Preis also came of age in an era of profound artistic and social progress in Vienna. Artists and architects were being hired by the city government to apply their talents to the betterment the lives of working class families just like Preis’s own. Between 1925 and 1934, the “Red Vienna” years, more than 60,000 modern apartments were constructed in Gemeindebauten – local community housing projects – by some of Vienna’s most influential modernists. In the Wiener Werkbundsiedlung of 1932 (Vienna Settlement Housing Project), the city’s best contemporary architects designed a group of small low-cost houses that created a public sensation. Preis was ensconced in an optimistic moment in progressive Viennese design – the Zweiten Wiener Moderne.

He soon fell in love with a young woman, Janina Vermiskoyiska Melzer, the daughter of a successful doctor. But Preis realized that if he was going to marry Janina and start a middle class family, the theater was not the best career prospect for him. Still interested in design, he followed a more reliable professional path.

In 1932 – the same year that the Werkbund housing exhibition opened – he enrolled in 1932 at the Vienna Technische Hochschule (TH) in order to study architecture. Because it was an engineering school, the TH emphasized architecture as a blend of functional considerations, structural logic, and aesthetics.

Preis worked as a draftsman for Universale Redlich & Berger in Vienna during his summer breaks. Redlich & Berger was a successful architectural and engineering firm that specialized in large-scale commercial, civic, and residential projects. As a Redlich & Berger draftsman, Preis would have become intimately familiar with modern systems of construction and, moreover, the ways that construction could be used aesthetically. His training there and at the TH would become key influences on his later work.

Escape from Nazi Vienna

Preis’s architectural career in Vienna came to a grinding halt when Austria was annexed by the German Nazi government on March 12, 1938. Through 1938, Preis witnessed the expulsion of hundreds of his Jewish classmates and professors at the Technische Hochschule who were either Jewish or not aligned with party ideals. Preis was not an observant Jew and as a boy he was fascinated with the Christian holiday festival pageantry. He had converted to Catholicism in 1936, and this conversion allowed him to finish his final spring semester at the TH. He graduated in 1938.

This was a short-lived reprieve. As the Nazis became radically stringent with their racial “purity” tests and because Alfred’s name appeared on the Jewish Community register at his birth, he made plans to leave Vienna. Not yet recognizing the threat that the Nazis posed to his life, his primary concern at the time was for his fiancé, Janina, who had no official citizenship in Austria. Her family had originally fled the Russian Revolution and she held no passport; the Nazis would soon begin their deportation of non-citizens. Recognizing their peril, the couple quickly married on March 14, just two days after the annexation.

The Nazis confiscated Jewish business and passed laws throughout the year barring Jews from the schools and from holding professional positions. Preis’s father’s auto business was one of the thousands confiscated by the Nazis throughout the year. Even though he was now Catholic, Preis was prevented from working as an architect. On Kristallnacht (The Night of Broken Glass) November 9-10, 1938, Jewish people were viciously attacked and murdered, and the city’s synagogues burned. The horror of this event no doubt convinced the Preises that they had to flee the city as soon as possible.

Using a directory of American architectural firms from the TH library, Preis wrote desperate letters to approximately fifty firms asking for a job. He received only one response from the Southern California architect, Lutah Maria Riggs. Although she had no work for him, one of her former employees, Connie Conrad and his partner Bernard Dahl, had opened an office in Honolulu and were in need of additional designers. Dahl & Conrad was one of Hawaii’s most progressive modern architectural firms. All that the Preises knew about Hawai‘i came from Hollywood, which portrayed the Territory as a tropical paradise; the couple was overjoyed at their good fortune.

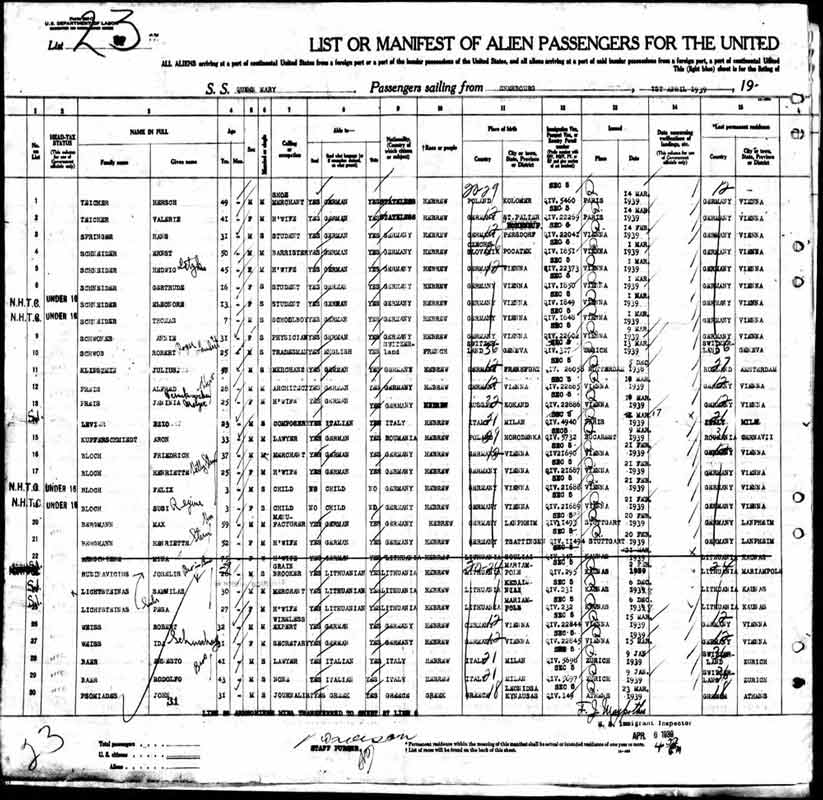

The Preis couple boarded the S.S. Queen Mary at Cherbourg, France on April 1st, 1939. His brother Fritz was also able to escape on another liner; and 16-year old Viktor Papanek – who would later become one of the US’s most influential social designers – was on the same boat. Although Alfred and Janina were now practicing Catholics, their passports still listed them as Hebrew as imprinted on the ship’s manifest, where they were but two of hundreds of other ethnically Jewish passengers fleeing Central Europe.

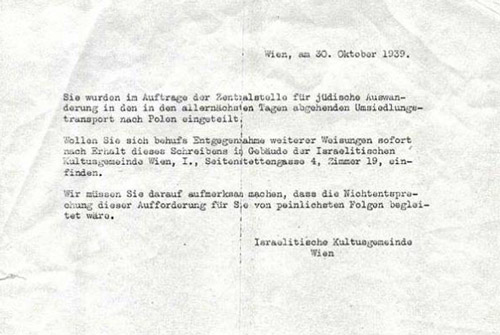

His parents did not enjoy the good fortunes of their sons. In the fall of 1939, approximately six months after Alfred’s departure, his father, Ignaz, was deported to a Polish “reservation” under the Nazi’s Nisko Jewish resettlement program for Viennese Jewish men. As it turned out, the desolate reservation had little food and shelter – SS officers forced some of the resettled men to cross into Soviet territory. In 1941, Ignaz mailed a photo to Fritz Preis in Nashville, Tennessee, most likely from a Soviet prison camp in Alma Ata. He was never heard from again. For a short time, their mother remained at her fourth district apartment before she was expelled to the Jewish ghetto in Vienna’s second district. She was ultimately deported to Riga and may have been one of the many older and infirm Viennese Jews who were gassed to death in the transport vehicles before they even reached the concentration camp. Ultimately, all but one member of Preis’s extended family would be murdered at Auschwitz. Preis likely never knew any of the details of his family’s demise, a heavy burden to bear for one who escapes. Instead, he kept these tragic losses to himself, never discussing them in any public forum. They remained his private sorrow.