Klimt and his Patrons

in "Vienna of 1900"

Even today, the world remains fascinated with the idea of “Vienna around 1900,” with all its peculiarities and diversity. The Jugendstil painter Gustav Klimt, who was supported and admired by his collectors and patrons, is central to this interest.

The modern art market developed relatively late in Vienna, which meant that the personal relationship between artist and collector could persist for longer. Vienna has always had important collectors, such as the imperial family, old nobility, and the roman-catholic church. Around 1800, as the new economic and intellectual elites were forming, this relationship between “court artist” and client changed. Circles of art collectors, who were not part of any aristocracy, started developing and became interested in contemporary art—at a time when there was no consensus regarding what artists were meant to do.

Following his “scandalous” years and the turmoil around the Beethoven Frieze and the faculty paintings, Klimt started distancing himself more and more from public clients at the beginning of the new century. Important circles of industrial elites and the bourgeoisie, in particular from Vienna’s Jewish population, began to form around the celebrated master. However, Klimt also received numerous assignments in connection with the Secession, founded in 1897, as well as from the Vienna Workshop, formed in 1903, and its co-founders Josef Hoffmann, Kolo Moser and Fritz Waerndorfer. Many notable figures were part of this association of collectors and artists, among them Sonja Knips, Karl Wittgenstein, Eugenia and Otto Primavesi, Adele and Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer, Berta and Emil Zuckerkandl, and Carl Reininghaus. Also included were Serena and August Lederer, arguably the most important Klimt collectors. These people were the first owners of a great number of the artist’s most famous paintings, as well as many of his works on paper.

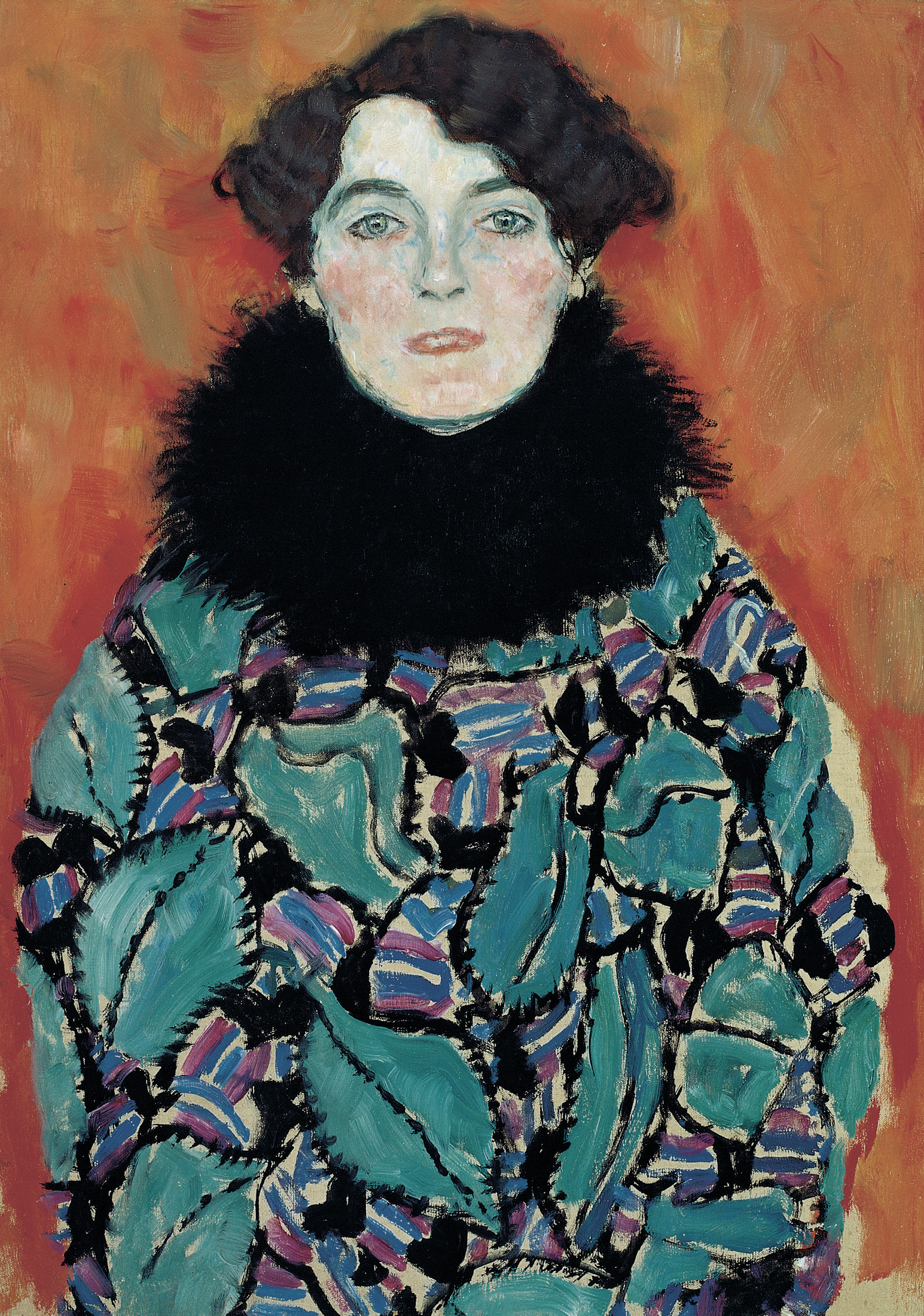

On multiple occasions, they gave very specific commissions to the artist—such as painting a portrait of a wife or of a daughter. Today, 25 portraits of women can be identified precisely. No other Viennese painter was able to satisfy more skilfully the longing of the Viennese bourgeoisie for nobility, or to more masterfully walk the thin line between ornament and eroticism than Gustav Klimt.

Some of Klimt’s patrons also supported him in financially difficult circumstances or, alternatively, helped to save the artist’s “cultural artefacts.” It is thanks not only to Carl Reininghaus, but especially to August and Serena Lederer that the “Beethoven Frieze” was saved after the closing of the Secession Exhibition of 1902. Klimt’s faculty paintings “Jurisprudence” and “Philosophy” were also part of the Lederer family collection until, due to the war, they were destroyed by fire in 1945 at Immendorf Castle in Lower Austria.

Fritz Waerndorfer, financial backer of the Vienna Workshop, donated the interior and furnishings of Gustav Klimt’s studio, much of which is preserved to this day. To honour the master of modernity, Waerndorfer was going to pay for a series of murals for Klimt’s studio in the 8th district of Vienna, Lerchenfelder Straße 21, and to equip the studio with precious furniture, designed by Josef Hoffmann and built by the Vienna Workshop. However, Klimt, who was then actively working and preparing for the Secession exhibition, became aware of the “surprise.” He asked that the “refurbishing” be done after the closing of the exhibition. Klimt’s favourite photographer, Moritz Nähr, documented the new interior for posterity.