Alfred Preis

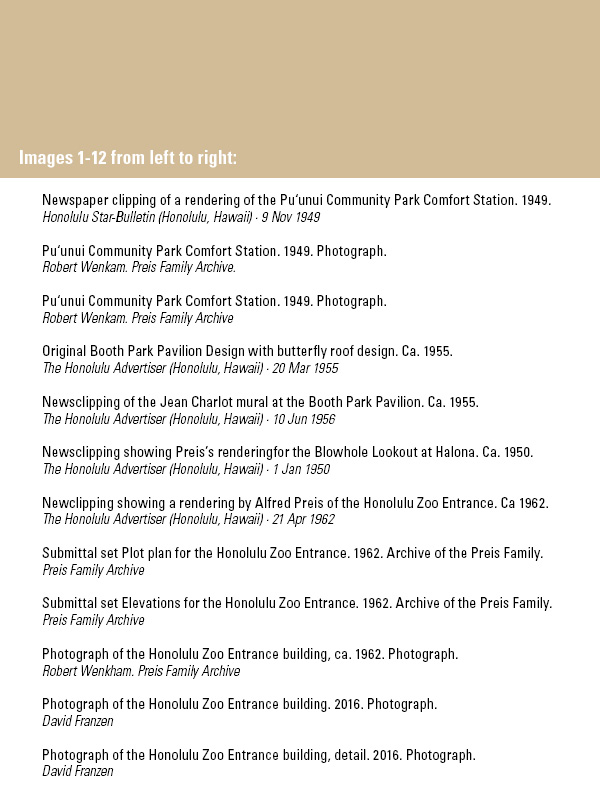

Public Parks and the Honolulu Zoo Entrance (1947-1962)Through the 1950s and 60s Preis created regionally inspired designs for Hawaii’s public architecture. In 1938, the architectural critic, Lewis Mumford, wrote an influential essay Wither Honolulu (1938) in which he argued that the Honolulu Planning Commission was not doing enough to help residents enjoy the outdoors and that the city and county needed to take a more active role in designing Hawaii’s parks. Following some of Mumford’s ideas, Preis committed himself to creating spaces of community recreation and to foster the enjoyment of the outdoors. In a series of modest and economical postwar projects, including the famed Halona Blowhole, Pu’unui Park, Booth Park, and the entrance for the Honolulu Zoo, Preis forged an understated and regional Hawaiian modernism, which did not overshadow the beauty of the landscape and sea. He vigorously attempted to merge architectural design with the natural environment in a way that showcased Hawai‘i as a place of paradise.

In the early 1950s, Preis was active in trying to reform Hawaii’s “scenic controls.” Joined by his colleague, the architect Hart Wood, he argued before a congressional committee that the territory needed to implement a constitutional provision regarding architectural “sightliness” to regulate the appearance not only of new buildings, but also beaches, parks, and playgrounds in order to preserve Hawaii’s majestic “creations of God.” Preis believed that Hawai‘i had two main assets – its breathtaking beauty and its tropical climate – and that the government had a duty to protect and enhance natural resources and to actively promote good design in civic and landscape planning. His strong feelings may have come from the fact that he was raised and trained in one of Europe’s most esteemed artistic centers, where urban development was tightly controlled by the government. In Hawai‘i planning and building was driven by corporate and private development. Although significant legal measures he envisioned against “unsightliness” were ultimately dismissed, in his own work Preis promoted the cause of good environmental design for both locals and for tourists.

Preis embraced public interest design. He was an increasingly sophisticated and respected designer, but he was not an architect who siloed himself by designing solely for the elite. Instead, he enthusiastically accepted modest public commissions with restricted budgets, which benefitted the community at large. Preis believed that designing public environments was a democratic process and that his primary responsibility was to respond to his clients – the public – who would ultimately use his designs.

In this, Preis was well ahead of his time. In his design process for public parks, he directly involved the community. In this, his work preceded the “community design” movements of the 1960s and 1970s by over twenty years. He also brought his community design efforts to the field of architecture at large, giving an address on “Civic Planning and Community Cooperation” at a California convention of the American Institute of Architects.

The Halona Blowhole (1949)

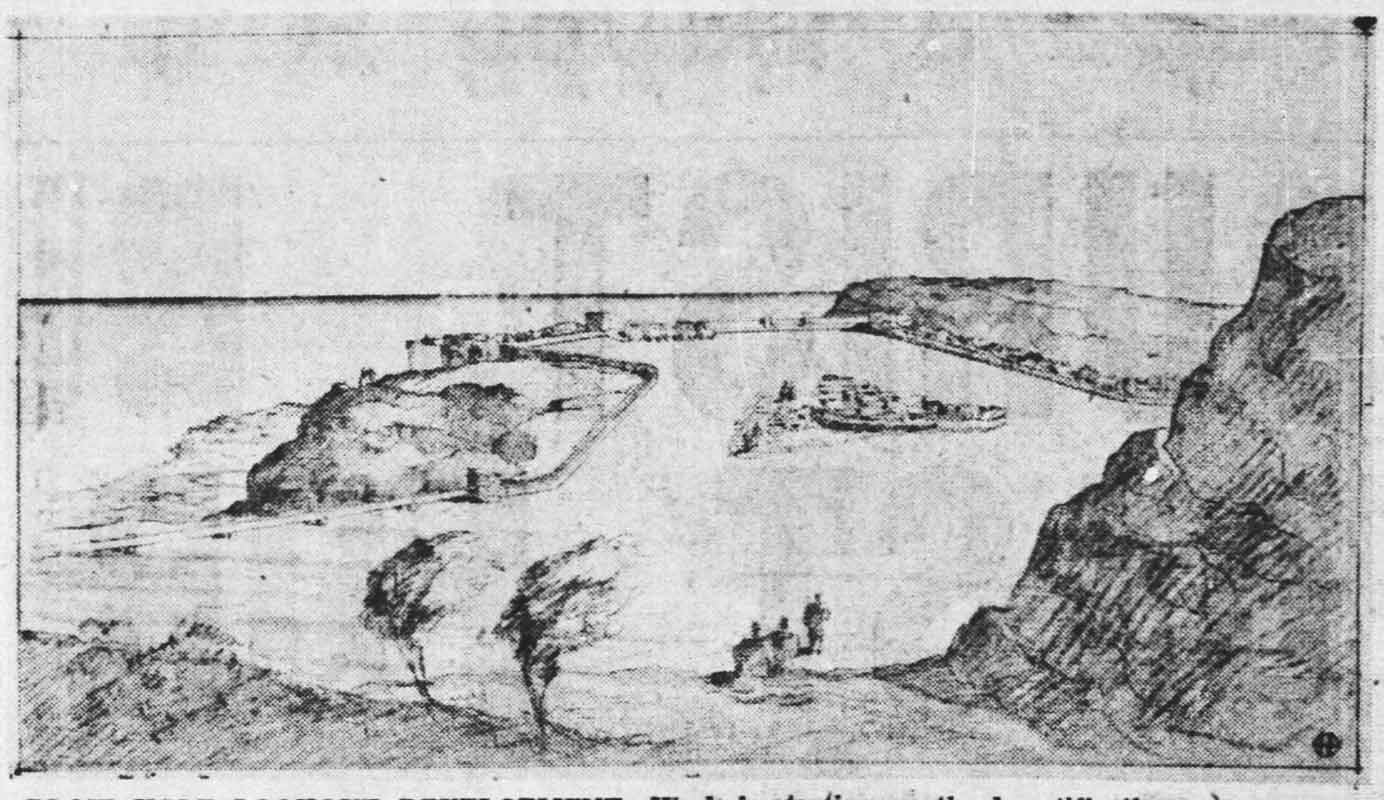

Preis’s first project of public landscape design was a parking and viewing area for the Halona Blowhole at O’ahu’s most southeastern tip. The Blowhole is regarded by many as the most magnificent of several such geological phenomena on the island of O‘ahu. It derived its name from the large jets of water expelled from incoming surf that travels through an ancient, narrow lava tube in the rock; the resulting sprays resemble those of the humpback whales who gather annually to breed near the islands’ coastlines. The Blowhole is situated on a winding road cut along one of the island’s most scenic stretches of coastline, where cliffs of reddish-black lava drop precipitously into the ocean. Prior to Preis’s intervention, the site lacked ample parking and viewing platform to accommodate the increasing number of tourists who came to witness its power.

Preis designed an unobtrusive paved parking area enclosed with a lava rock wall and a viewing platform located directly above the Blowhole. He planned the walls and landscape to induce the growth of native plants, such as the sprawling yellow-flowered ‘ilima shrub. Preis’s very modest architectural interventions created a focal point for visitors to witness nature’s majesty. Not only that, but in the winter season, visitors might also be treated to glimpses in the distance of the whales themselves spouting through their blowholes.

Pu’unui Park and Booth Park (1947-1956)

In 1947, Preis was commissioned to design the community buildings for two parks, Pu’unui Park and Booth Park. The parks were located in new areas of suburban development to the north and east of downtown Honolulu to create family recreation areas nearby the growing new clusters of single-family houses.

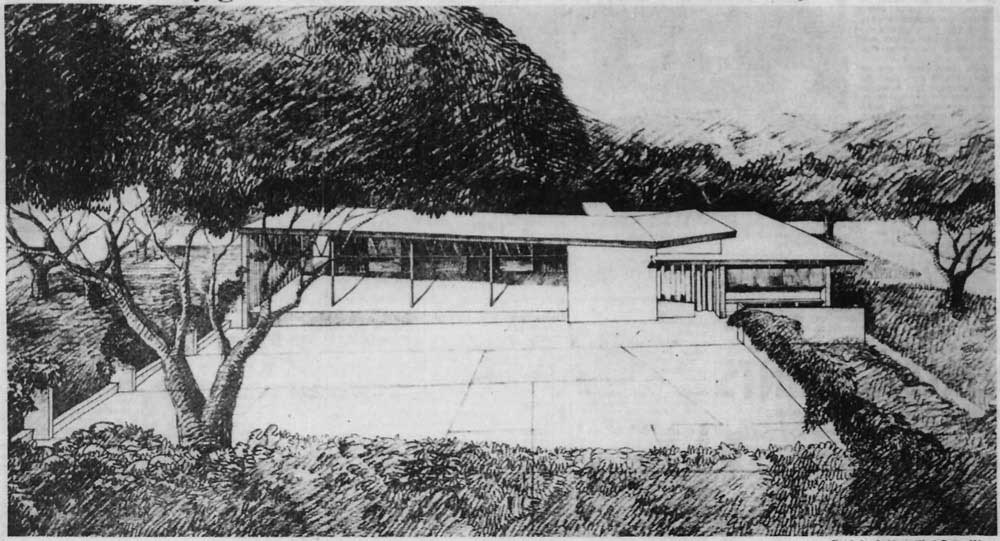

The Pu’unui community association settled on a park site perched on a picturesque hilltop overlooking the city and asked Preis to design the park’s community building. Drawing on his recent community planning experiences with the Veterans Village project, Preis sat down with community members to hear what the residents wanted before drafting his plans. Following their advice, Preis created a multipurpose park building as a modest, single story structure with a flat roof. A published drawing shows that he originally envisioned a structure composed of thin, horizontal courses of brick or hollow tile masonry, but later alterations now sadly obscure Preis’s original design.

An angled, upper roof with a row of clerestory windows captured cooling trade winds from the mountains. Thin pilotis supported the wide porch roof, giving it a floating quality. These touches diminished the building’s overall mass and blended it with the hilltop landscape. In this way, his design used simple, modernist idioms that did not overshadow the park’s terrain and greenery.

Wide interior rafters following the angle of the roof created a dynamic line, giving the elevation an exciting asymmetry. At some of the corners of the interior walls and supporting pillars, Preis set the courses of masonry slightly askew in alternating rows, which fostered a dynamic dialogue with the angled roofline. Such aesthetic touches infused the room with moments of subtle movement and energy that broke with the rigid rectilinear surfaces – and all at a very low cost.

Booth Park (1956)

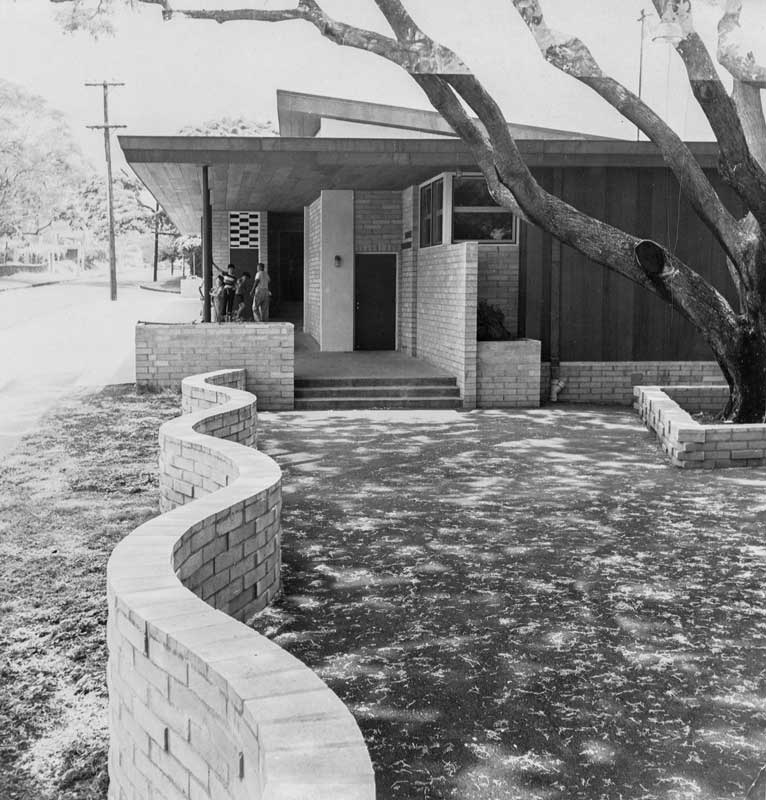

Preis was also tasked with designing the community building at Booth Park in Pauoa Valley, a large area covering over two square blocks at the center of a new development of suburban houses. Low mountains rise visibly from the terminus of the valley not far away to the north and west. Groups of existing, mature trees served as the nucleus of the park’s collection of new buildings, paths, and picnic areas. The park coalesced as a green, grassy expanse, with its edges punctuated by large monkeypod trees, whose canopies created an inviting and dappled shade. The park buildings were modest, due to the necessarily low budget for the project ($35,000), but Preis made the best of it, preferring that the park’s abundant mature trees and its jewel-green grass speak a bit more loudly than his architecture.

Preis’s original design cultivated a midcentury twist, with a subtly angled and dynamic “butterfly” roof and lithe pilotis over an open community pavilion. The structure was fronted with a large and tranquil paved courtyard. This use of the butterfly roof ten years prior to its widespread adoption on the mainland deserves special note. The butterfly roof would later achieve popularity in many mainland houses and other buildings, in part because its wing-like form spiritually captured the pervasive sense of economic, technological, and social progress enjoyed among many in midcentury United States. In Hawai‘i the form had a regional resonance, since it echoed and abstracted the forms of the island’s dramatically angular mountain peaks and ridges.

Unfortunately, Preis’s pavilion design was modified substantially before its completion in 1956, in favor of much less graceful concrete piers and a more conventional flat roof. But Preis found other opportunities for aesthetic exploration: the supporting rafters were bulkier than necessary, and so maintained his conviction that quality architectural decoration, especially in low-cost buildings, could be easily achieved through practical construction.

Honolulu Zoo Entrance (1962)

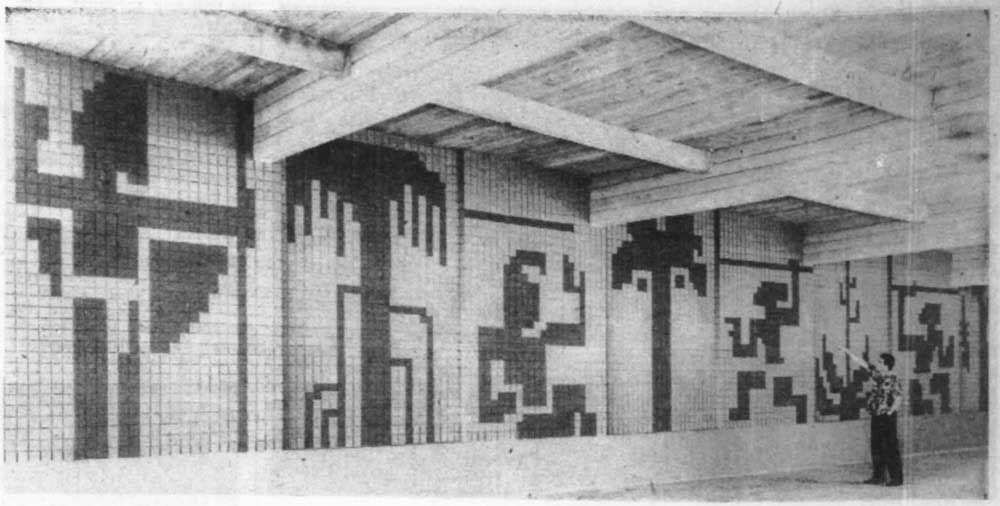

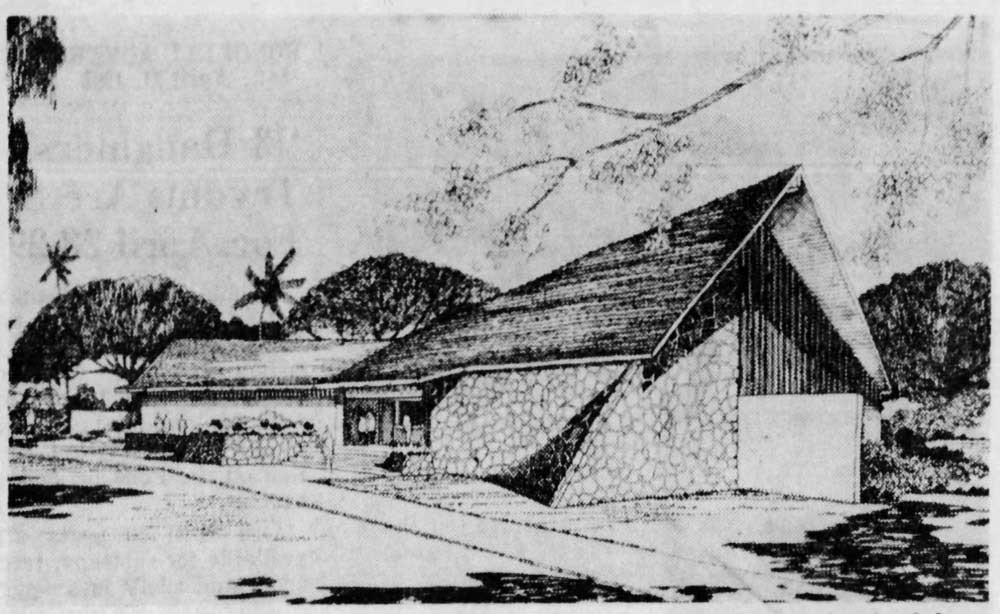

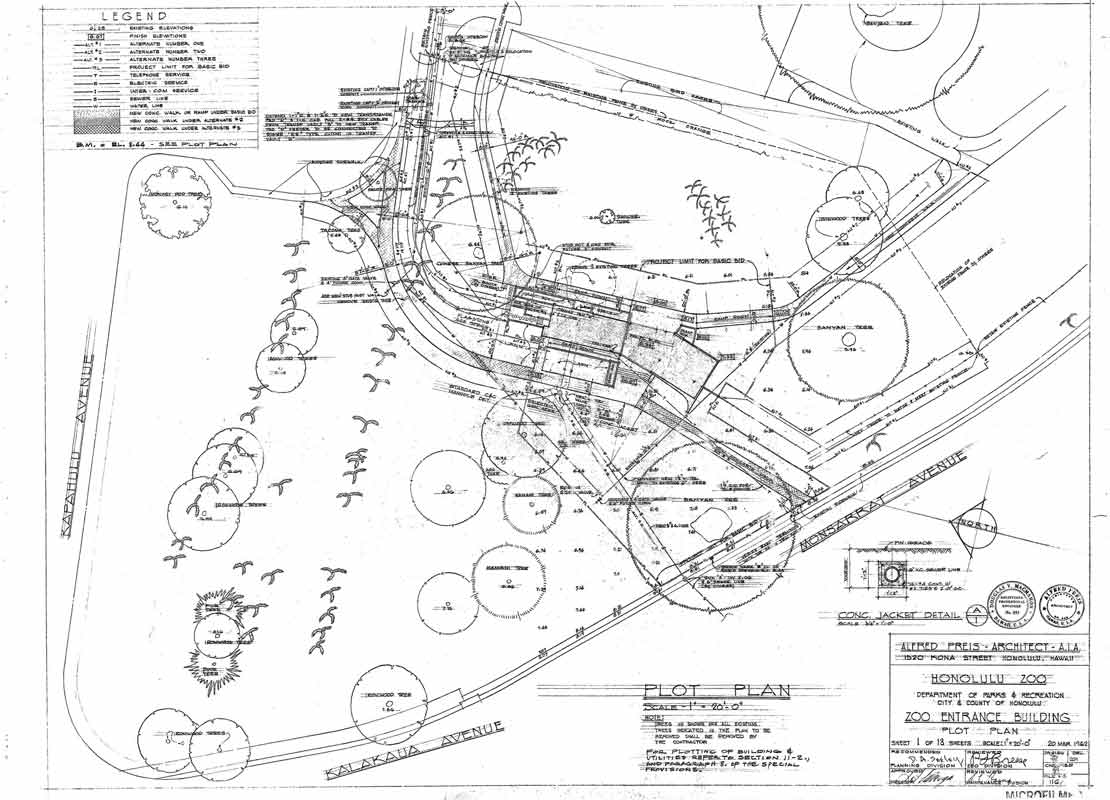

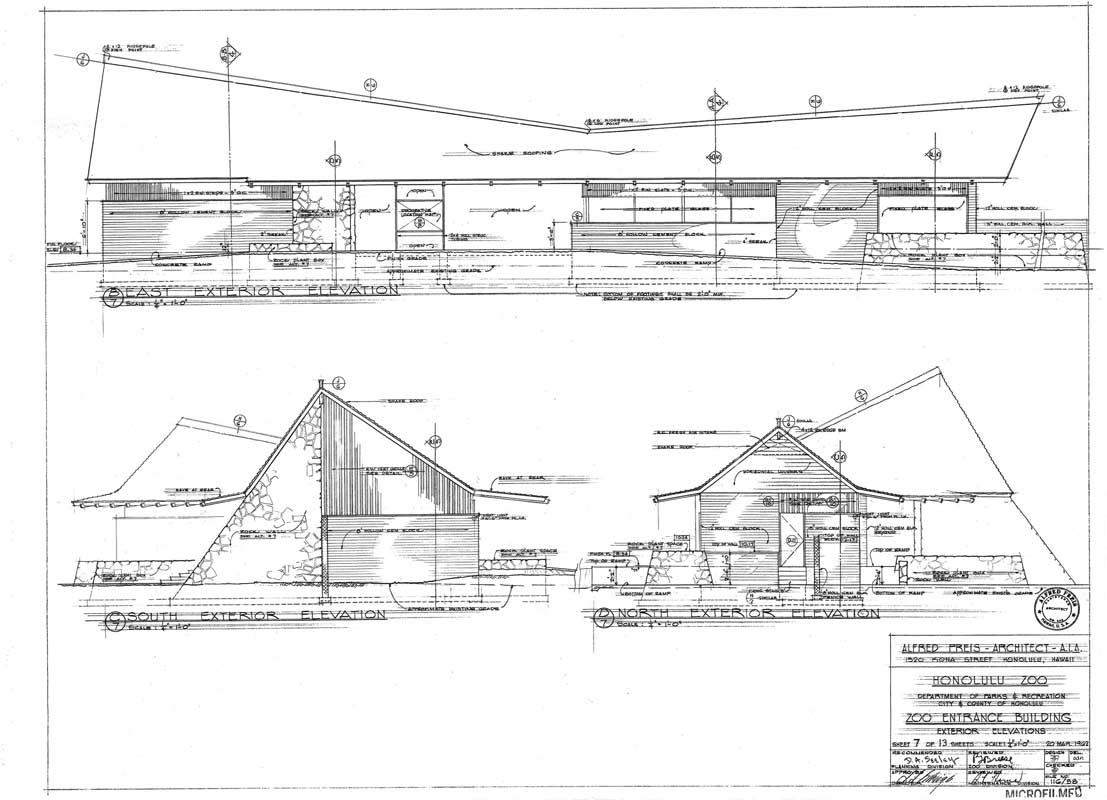

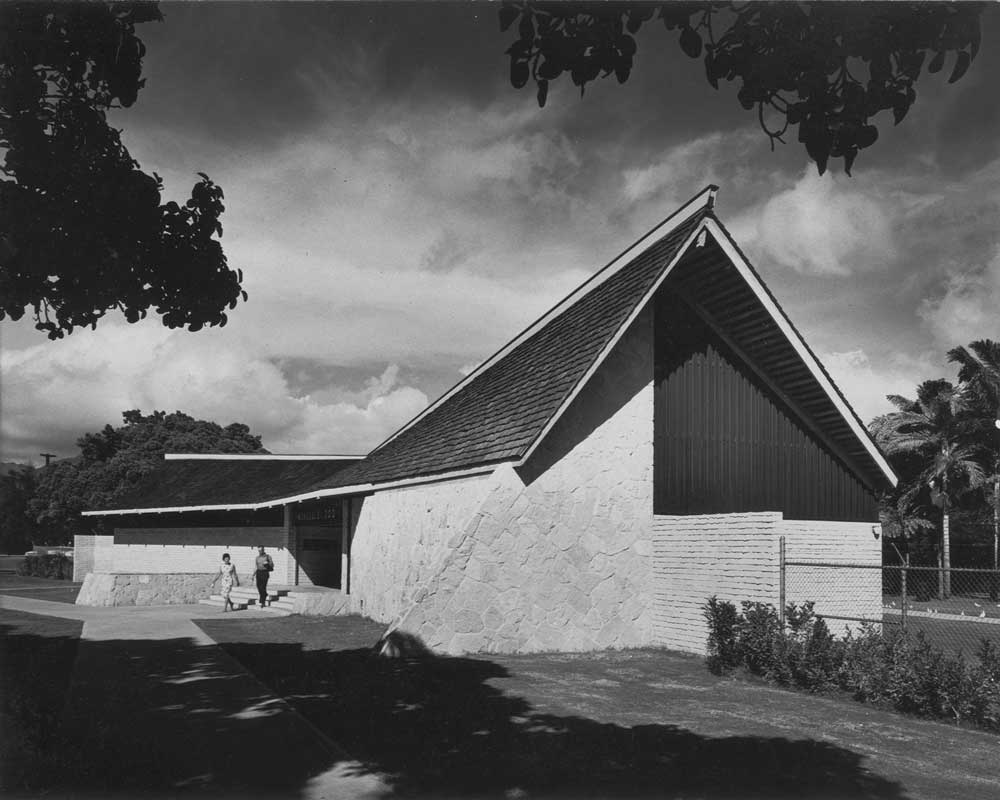

Preis’s entrance building to the Honolulu Zoo was perhaps one of his most visible commissions for both Honolulu residents and tourists. After Hawai‘i became a US state in 1959, the early 1960s were a booming time for tourism to the islands. Local designers sought to market Hawaii’s exoticism and various, generalized interpretations forms and arts of Native Hawaiian and Polynesian cultures. Preis’s design for the Honolulu Zoo, however, transcended kitsch. While it was certainly commercially appealing, Preis applied the regional architectural ideas that he had been developing over the previous decade.

The building showcased Preis’s tendencies towards public buildings with a distinct horizontality that blended with the landscape. In the Zoo, Preis relished unusual angles creating a centerpiece to draw visitors into the complex set in a busy area directly across from Waikiki Beach. He mixed materials – wood, tile, concrete, and stone to create a vividly textural experience. The asymmetrical V-shaped building boasted an A-frame roof derived from the Hawaiian hale (house). The wide roof was the most dramatic and visible element of the structure; Preis covered it in rough, wooden shingles to emphasize rusticity and a connection to Hawaii’s material environment. The eaves at each end extended broadly over the body of the building, giving it a remarkable dynamism, as if the roof would continue to spread broadly out over the land. Preis used his signature butterfly roof, which dipped sharply at the middle over the ticket counter and main entrance giving it a perspectival effect. An angled staircase of light-colored paving stones rose from the ground to give the building a ceremonial sensibility with a planter full of tropical vegetation to one side. For many years, the building was under threat of demolition, when a new entrance was built to one side to accommodate an increasing number of visitors and business functions. However, due to the strident efforts of local preservationists, this signature example of midcentury Hawai‘i regionalism has recently been rescued.