Alfred Preis

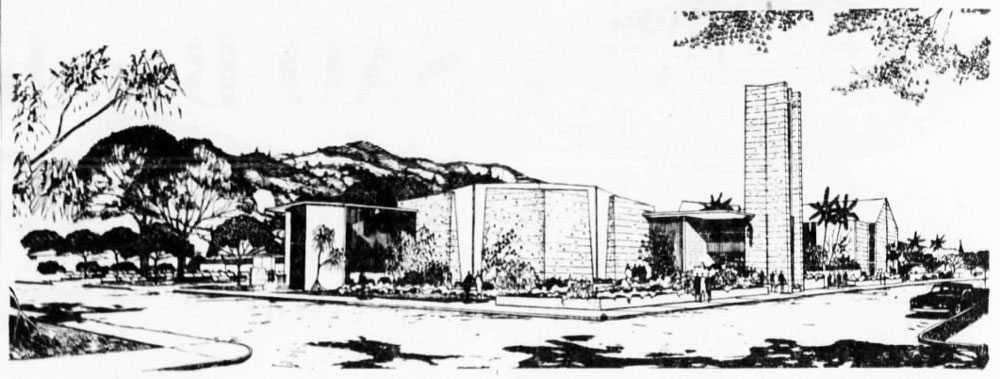

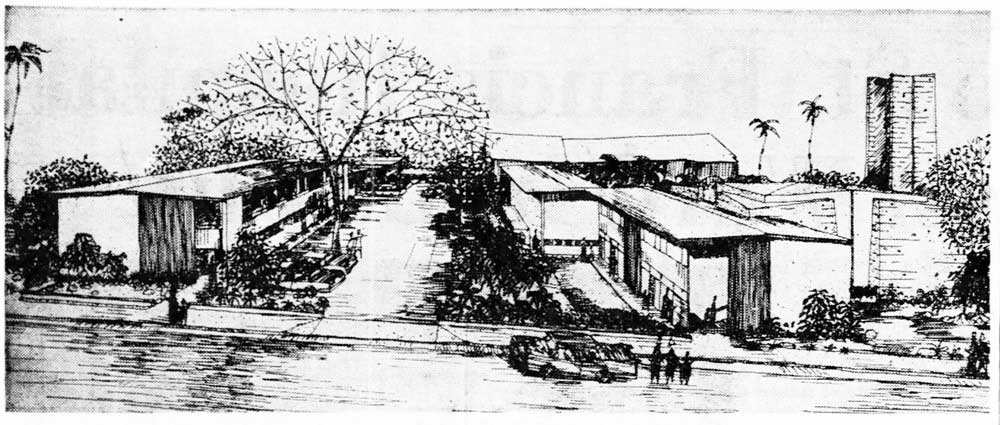

First United Methodist Church (1949-1954)Preis was commissioned in 1949 by the congregation of the Honolulu First United Methodist Church to design a new sanctuary, children’s center, and administrative building on a large site near the Honolulu Academy of Art, and to modernize and redesign the entire block to create a more community-focused environment. Although his full site plan would not be completed, Preis’s design was the first significant modernist church on the islands. The First Methodist Church sanctuary was one of the first major public buildings on the islands to definitively adopt elements of pre-contact, indigenous Hawaiian architecture in a forthright way. He utilized the form and logic of one its most recognizable structures – the hale (house). His visionary design would have a lasting impact on island church architecture through the 1960s and 70s and it paralleled some of the most avant-garde mainland worship spaces constructed in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Preis began designing in 1950, ground was broken in the fall of 1951, and the first structure, the kindergarten, was completed in the summer of 1952. The kindergarten had space for infant and nursery care, a preschool classroom, two classrooms for elementary school-aged pupils, a greenhouse, and caretaker’s quarters. Incorporating elements familiar to Hawaii’s large Chinese immigrant population, the rooms opened onto an open play court that sheltered the children from the street.

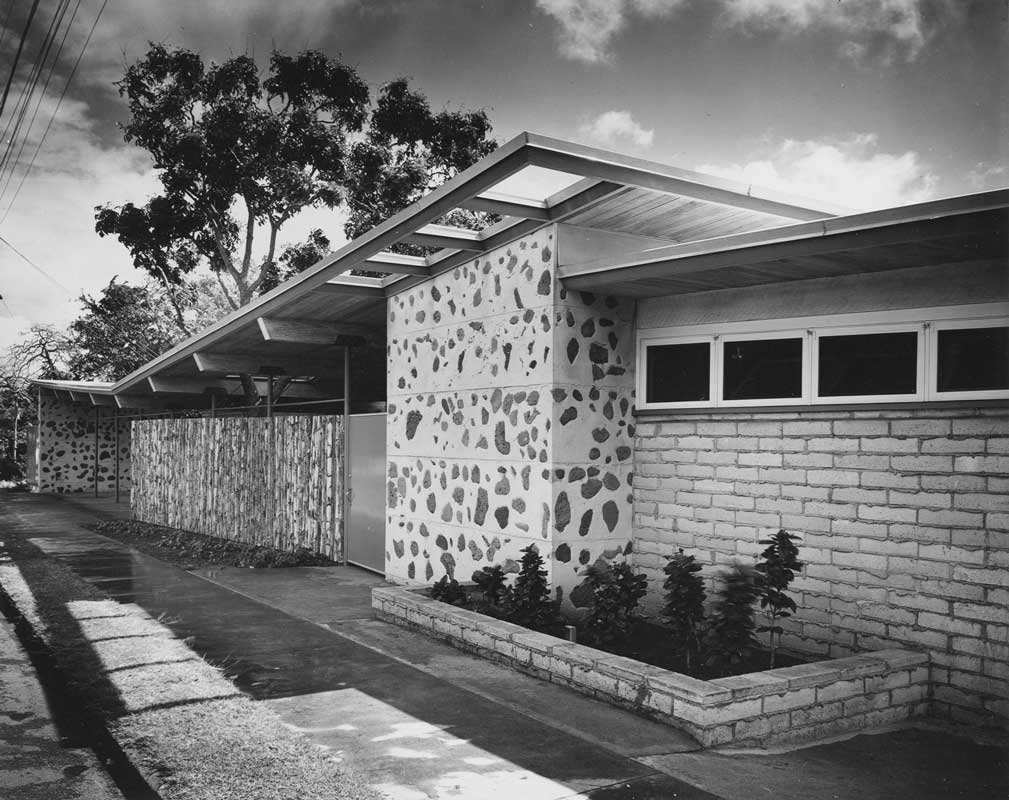

Preis also used the local environment for striking aesthetic effects. He was no longer content with the smooth surfaces of the European and Viennese modernist and Streamline Moderne styles that drove much of his earlier work, since they plainly defied the dramatic and irregular shapes and surfaces of O‘ahu’s landscape. Brick walls that emphasized horizontal lines were interrupted with vertical, rectangular projections in lava-studded concrete and rough, wooden screens.

In the children’s center, he created concrete walls with exposed lava rock aggregate. But he also added a new decorative and constructional element. The building’s main walls were of brick courses with an excess of mortar pressed between them. In a dramatic rejection of the smooth surfaces of the International Style, the mortar oozed out and thickly enveloped the edges of each brick in unpredictable, and somewhat messy formations.

But when viewed from several feet away, this technique gave the flat walls an appearance that resembled the warp and weft of roughly woven textiles. These heavily textured brick walls were reflective of his approach to creating decoration with inexpensive and locally available materials an relate directly to Gottfried Semper’s idea of Bekleidungsprinzip (principle of architecture ‘dress’).

The church broke ground for the new sanctuary in the spring of 1953 and was largely completed by 1954. The sanctuary plan was a large hall with a seating capacity of between 750-1200. In an unusual design move, the sanctuary walls angled slightly inwards to meet a wider volume that housed the pulpit and ancillary rooms, including as the pastor’s study and a room for wedding brides. This trapezoidal plan, which was enhanced by seating that was also angled inwards towards east end, focalizing the congregation on the pastor and choir stage.

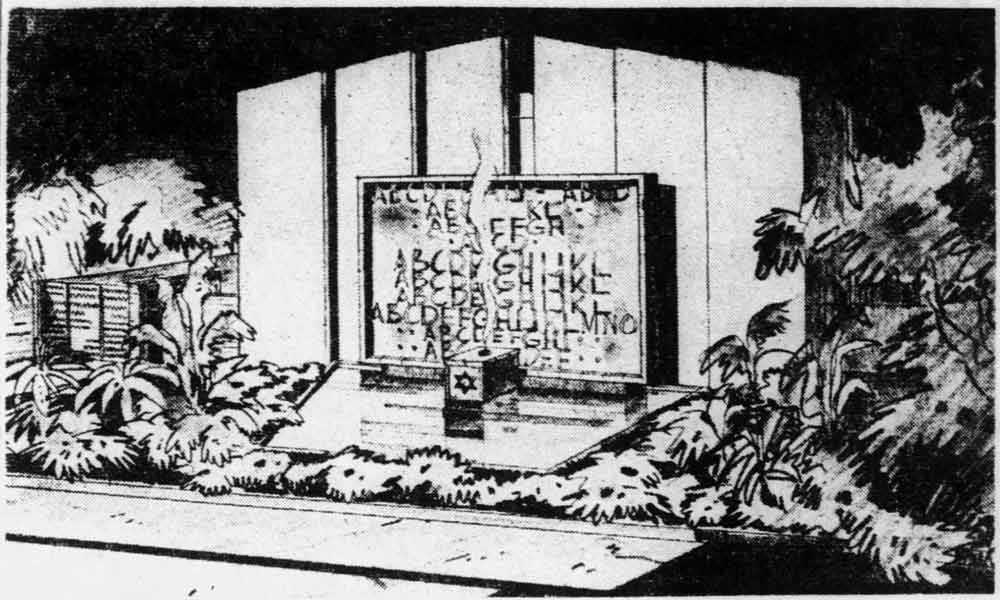

The church continues to defy expectations with its entry sequence. Congregants accessed the building through glass doors at the side of the sanctuary across a central courtyard. In the front façade, Preis repurposed his concept for an earlier synagogue’s facade, designing it as opaque gable-end. In effect, the sanctuary was simply sliced open at one end and walls of coral sand concrete and lava rock aggregate were inserted into the void. Instead of creating a special façade that was visually independent of the gathering space within, Preis eliminated solid walls along the aisles and instead, the pitched roof was laterally supported by these pillars set at wide intervals. The open-air sanctuary took advantage of the cooling effects of the concrete, the shading of the vines, and the trade wind breezes. Contemporary commentators noted the distinct feeling that one was “worshipping outdoors” while in the building, which evoked pre-contact indigenous religious practice.