Alfred Preis

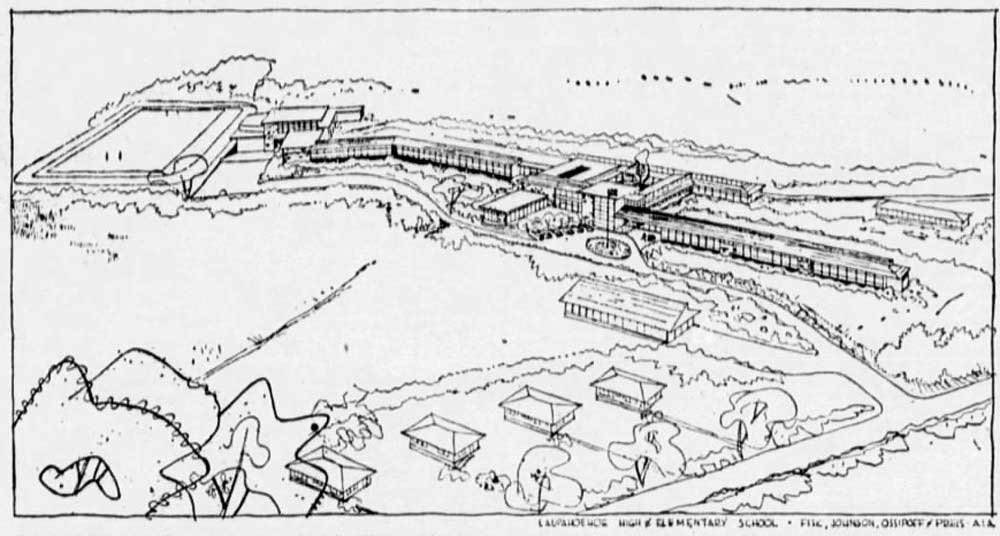

Laupāhoehoe Elemetnray and High school (1948-1951)Preis’s first landmark achievement of regional Hawaiian modernism was the Laupāhoehoe School located on northeastern coast of the island of Hawai‘i near the port town of Hilo. An Associated Architects commission, it represented a remarkable turn in his work away from more prosaic International Style and streamline moderne idioms toward a specifically local aesthetic. But it nevertheless retained the qualities of modern spatial planning and constructional ornamentation that he had absorbed in Vienna.

The building – a new construction as a response to the devastations of the deadly tsunami of 1946 – was set high on a hill between two plantation villages and was surrounded by green pastures overlooking the vast Pacific. Climate and site for Laupāhoehoe School, according to a critic for the Architectural Record, “played an unusually large part of the design.” It was laid out in a “ribbon” plan, a lengthy, horizontally disposed composition that stretched broadly over the windy, and frequently very rainy, hilltop.

The façade was articulated with a wide expanse of glass windows, set in a grid-like pattern of mullions, however, glass was counterbalanced by a generous use of rough and earthy concrete, with exposed volcanic aggregate.

Preis’s use of local materials for the school was the result of necessity – the main road to the site had been heavily damaged by the tsunami. Although wood construction would have been the most economical option for building, new building code regulations stipulated that wooden sections had to be separated with concrete firewalls, which appear throughout Preis’s design.

Large pieces of lava rock aggregate, found in abundance at the nearby shoreline, replaced nearly three-quarters of the mass of reinforced concrete. Preis also used the trunks of ʻōhiʻa trees liberally through the building. ʻŌhiʻa is abundant across the island and is an important material in Native Hawaiian culture and mythology.

The local materials serve for grand aesthetic effects, exhibiting that structure could also be used as decoration. Exposed roof trusses ornamented multi-purpose rooms. The cafeteria’s roofline was set in a striking, butterfly V-shape, punctuated by a central line of supporting ʻōhiʻa columns. The exterior corridors were enriched by innovative connections and contrasts between ʻōhiʻa, conventional wooden construction, and Preis’s lava-concrete slabs. Each space or room was spatially and formally distinctive, but all were wedded through his consistent use of the local materials of ʻōhiʻa and volcanic aggregate.

The concrete foyer, its staircase, and other communal spaces were naturally lit. Bands of clerestory windows admitted sunlight, but their elevated position also created a cooling dimness that sheltered students from direct exposure to the intense, equatorial glare. The rooms were also well ventilated to take advantage of the directional patterns of the trade winds, which swept across the islands and provided some respite from the relentless humidity.

The school was a highly successful, marriage of two seemingly disparate impulses. It was rustic and roughly local, relatively economical, and yet almost lavishly, modern for a small school in a plantation community.