After World War Two

Exile, Return, and New Beginnings

Following Austria’s liberation by the Allies, the country’s Trümmerfrauen [rubble women] bore the main burden in Austria’s reconstruction (even if this role was often unduly romanticised). Other women worked as journalists or artists to help their homeland recover. But much knowledge, strength, and creativity was ultimately lost because Austria neglected to officially invite important women emigres to come home.

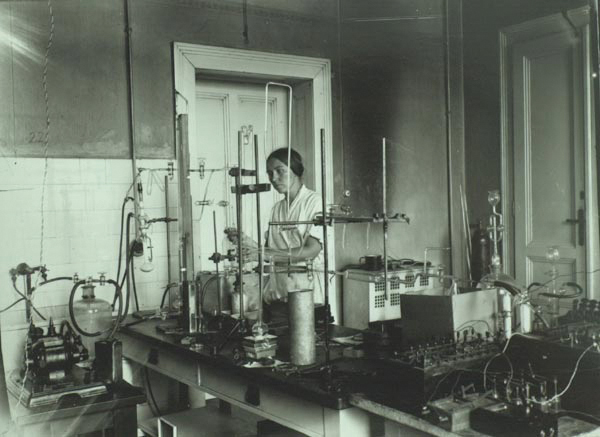

Marietta Blau, nuclear physicist (1894–1970)

“A woman and a Jew. Both at once is too much.” It was with this crushing pronouncement by a public employee at the University of Vienna that Marietta Blau’s application for a teaching post was rejected—all the more crushing because Blau had every prerequisite for a successful academic career. The hurdles that Marietta Blau encountered over the course of her working life and the absence of recognition during her lifetime exemplify the plight of a great many gifted women researchers of her era. In 1914, she passed the Matura at a private academic secondary school for girls in Vienna and began studying physics and mathematics. After receiving her doctorate in 1919, she found employment as a scientist in Frankfurt and Berlin but ultimately returned to Vienna, where she worked without pay at the Institute of Physics. There, she participated above all in the development of photographic methods capable of detecting individual subatomic particles, work that was pioneered in Vienna. Due to her Jewish descent, Marietta Blau was forced to flee the country in 1938, after which Albert Einstein soon succeeded in finding her a position at the Instituto Politécnico Nacional in Mexico City. She moved on to the USA in 1944, where she continued her work at universities in New York City, on Long Island, and in Florida. She was twice nominated unsuccessfully by Erwin Schrödinger for the Nobel Prize in Physics. By then, Blau’s health was already deteriorating due to years of radiation exposure. In 1960, she returned to Vienna, where she—once again, without pay—continued her work at the Institute for Radium Research until 1964. In 1962, the Austrian Academy of Sciences awarded her its Erwin Schrödinger Prize—but did not accept her as a member. And in 1970, Marietta Blau—by that time completely destitute—succumbed to cancer in Vienna.

Stella Kadmon, theatre director (1902–1989)

Following initial engagements at theatres in Linz and in the Moravian city of Ostrava, Max Reinhardt Seminar graduate Stella Kadmon was encouraged by the Austrian comedian Fritz Grünbaum to try her hand at stand-up comedy. Though a planned revue together went unrealised, Stella Kadmon did debut as a chansonnière with songs by Grünbaum at the Viennese cabaret “Pavillon” in 1926, after which she appeared successfully at well-known cabaret venues in Vienna, Munich, Berlin, and Cologne. In 1931, Kadmon co-founded Vienna’s first political cabaret, called “Zum Lieben Augustin” and situated in the basement beneath Café Prückl (which still exists today). She headed this venue until the National Socialists shut it down in 1938, at which point Kadmon—as a Jew—was forced to emigrate. Upon arriving in Tel Aviv, Kadmon founded the Hebrew-language cabaret “Papillon”, where she also held German-language musical evenings and readings. And in 1947, following her return to Vienna, she once again became head of Zum Lieben Augustin (which had already been reopened by Fritz Eckhart) and made the establishment into a home for avant-garde theatre. Following a successful production of Bertolt Brecht’s Furcht und Elend des dritten Reiches (Fear and Misery of the Third Reich) in 1948, Kadmon also gave her theatre a new name: “Theater der Courage” [Theatre of Courage], and she was to head this establishment, which went on to lead the way for Austrian small-scale performing arts as a whole, until it closed in 1981.

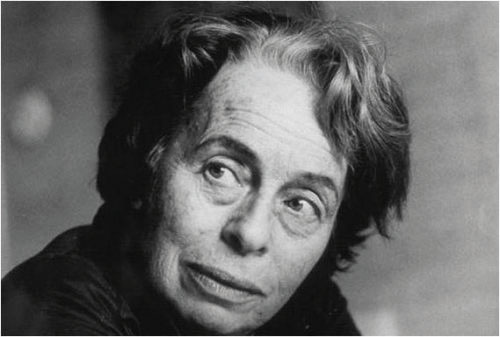

Hilde Spiel, author (1911–1990)

After passing her Matura at Eugenia Schwarzwald’s school for girls, Hilde Spiel went on to study philosophy, earning her doctorate in 1936. Alongside her studies, she had already published her first novel: Kati auf der Brücke [Kati on the Bridge], a deep-reaching contemplation of love in which she demonstrated how she had seen through society’s differentiation between the sexes. 1936 also saw her marry the author Peter de Mendelssohn, with whom she left for London due to Austria’s anti-Semitic policies.

Spiel became a British citizen in 1941 and from then on made writing her profession. She soon became a well-regarded journalist and essayist, eventually contributing to major periodicals such as the New Statesman, Die Welt, and The Manchester Guardian. Her entire life long, Spiel was plague by a lack of time to do literary writing. But as a literary critic, she was enormously influential—helping authors such as Heimito von Doderer to achieve their breakthroughs—and she maintained long and turbulent relationships with Elias Canetti and Friedrich Torberg. In 1963, she returned to Austria, where her “favourite enemy” Torberg scuttled her election as president of Austria’s PEN Club. Spiel thereupon, in protest, transferred her membership to Germany’s PEN Centre, where she worked together with Heinrich Böll for the Writers in Prison Committee.

Minna Lachs, educator (1907–1993)

During the First World War, Minna Lachs and her family had to flee from her place of birth—the multilingual town of Terebovlia (in Galicia)—to Vienna. There, she studied German and Romance philology, psychology, and education, earning her doctorate in 1931 with a dissertation on German ghetto history. Soon, Germany’s annexation of Austria forced Minna Lachs to flee yet again. Together with her husband and their two-month-old son, she first emigrated to Zurich before continuing on to New York. In American exile, she worked in private schools, organised readings and discussions, and expanded her specialised knowledge as an educator. And in 1947, she returned to Vienna and continued her teaching career. As director (1954–1972) of the girls’ secondary school Mädchengymnasium Haizingergasse, Minna Lachs introduced modern, open-minded teaching methods and attempted to instil an appreciation for contemporary literature and political education. 1956 saw her became Vice President of the Austrian Commission for UNESCO, where she contributed her knowledge and years of experience in the educational field as chair of its Education Committee. And as editor of the anthology Und senden ihr Lied aus [And Send out her Song] (1963), she compiled poems by Austrian women from the 12th century to the 20th for publication, thus playing a central role in the rediscovery of numerous forgotten woman poets.

Mira Lobe, author (1913–1995)

“Or perhaps I don’t exist at all?”—asks Little I-am-me, Mira Lobe’s best-known children’s book character at the beginning of a search for an individual identity, a search that ultimately leads to the realisation: “Certainly I exist: I am me!” Mira Lobe authored nearly 100 books for children and youth, an oeuvre that was translated into over 30 languages and showered with awards. Alongside Little I-am-me, for which Lobe was awarded the Austrian State Prize for Children’s and Youth Literature, children all around the world know Lobe’s stories The Grandma in the Apple Tree (1965), Valerie and the Good-Night Swing (1981), and Die Geggis (1985). Due to her Jewish origins, she was unable to study German philology or art history in what had by then become National Socialist Germany. So in 1936, she emigrated to Tel Aviv, where she married the German actor and director Friedrich Lobe in the summer of 1940. There, she began working on a Hebrew children’s book that was also published in German later on with the title Insu-Pu, die Insel der verlorenen Kinder [Insu-Pu, the Island of the Lost Children] and, decades later, adapted for television as Children’s Island in Great Britain. Her husband Friedrich’s work eventually took the couple to Vienna, where Mira was to write the lion’s share of her books. Forty-five of these were done in collaboration with the illustrator Susi Weigel, lending them an appearance all their own. Together, Lobe and Weigel set new standards in literature for young people. And to this day, Mira Lobe’s stories teach young readers humanist values such as community, justice, solidarity, and understanding for outsiders and the weak while also highlighting the necessity of personal freedom, self-assertion, and criticism of authority.