Science is Feminine

Emergence from the Masculine Shadows

These days, prejudices against women getting an education seem absurd, but around 1900 they were viewed as facts: girls were said to be too superficial, the desire for a university education a sign of hysteria; the female brain was thought ill-suited to studying, and educated women supposedly became “man-ladies”. Today, by contrast, the share of women among those who qualify for university studies by passing Austria’s Matura examination stands at 60%.

1. Lise Meitner, physicist (1878–1968)

Since 1896, it had been possible in Vienna to take an external Matura that entitled those who had passed it to study at university. Lise Meitner took and passed her Matura in 1901. Following conventional training as a French teacher, she engaged in doctoral studies under Ludwig Bolzmann and earned her doctorate in 1906 with a dissertation on “Heat Conduction in Inhomogeneous Bodies”. She then went to Berlin and did research with chemist Otto Hahn in a basement lab, since—as a woman—she was not permitted to enter his institute at that time. She eventually became an assistant to Max Planck, despite Plank’s earlier opinion that “it would be a great mistake […] to admit women to academic study.” In 1926, Lise Meitner was appointed professor of particle physics, but as a Jew, she was barred from teaching in 1933 despite Planck’s intercession. Her subsequent exile in Stockholm saw her maintain close contact with Otto Hahn and coin the term “nuclear fission”, and she published calculations on the energy released by this process in 1939. This eventually led to the staunchly pacifist Meitner being named “Woman of the Year” and “Mother of the Atom Bomb” following explosion of the first atom bomb over Hiroshima. But in 1946, it was Otto Hahn alone who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering nuclear fission. Though Lisa Meitner was to log a total of 47 Nobel Prize nominations during her lifetime, she was ultimately be denied this honour. She did, however, become the first woman member of the natural sciences division of the Austrian Academy of Sciences.

2. Marie Jahoda, social scientist (1907–2001)

Marie Jahoda was born in Vienna to a family of assimilated Jews. In 1926, she began training as a primary school teacher at the newly founded Pedagogical Institute of the City of Vienna while simultaneously enrolled in the University of Vienna’s psychology and philosophy programmes. The early 1930s saw her teach at various Viennese schools. Following her anti-Semitically motivated dismissal as a schoolteacher, she focused increasingly on politics and the social sciences. The study Marienthal: The Sociography of an Unemployed Community (1933)—published with her husband Paul Lazarsfeld and Hans Zeisel—made her world-famous. Their detailed observations and surveys of 478 families showed that long-term unemployment leads not to revolts but rather to resignation and loss of self-esteem. In November of 1936, Marie Jahoda was denounced as a revolutionary socialist and, in the trial that followed, sentenced to three months’ imprisonment and one year of “protective detention”. But following massive international protests—the Marienthal study had been translated into numerous languages and received worldwide acclaim—Jahoda was released early. She left Austria within 24 hours, going first to Great Britain and later on, in 1945, to the USA, where she was appointed professor of social psychology at New York University in 1949. In 1958, she returned to Great Britain, where she became the first woman professor in the history of British social sciences to be entrusted with establishing a social psychology department. She was never invited to return to Austria.

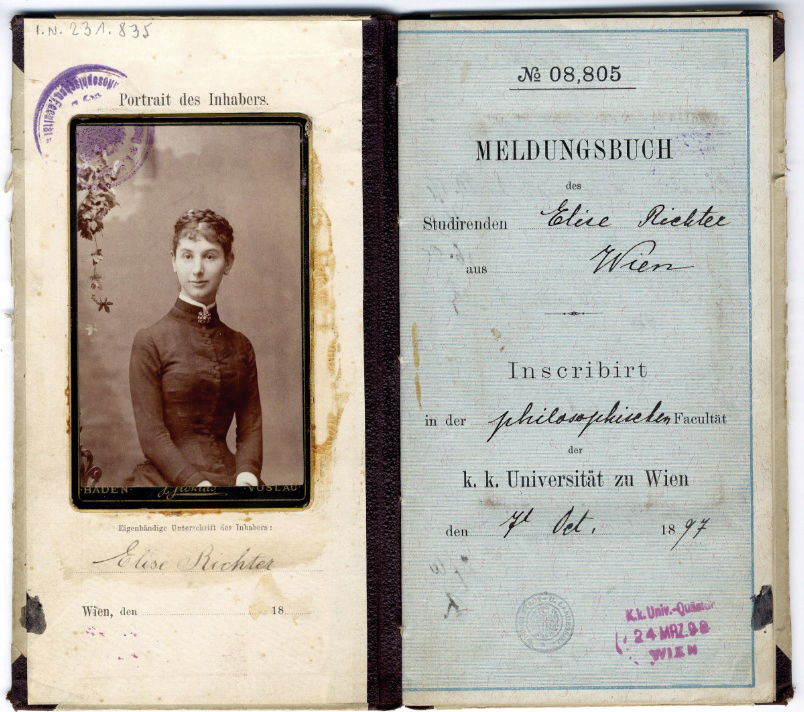

3. Elise Richter, romance philologist and university professor (1865–1943)

In 1897, Elise Richter became the first woman in Austria-Hungary to take the school leaving exam at the tradition-steeped Akademisches Gymnasium in Vienna, whereupon she enrolled at university to study Romance philology, general linguistics, classical philology, and German philology. She also became the first woman to earn her habilitation at the University of Vienna, thereafter going on to become Austria’s first non-male senior lecturer. But she would never attain a full professorship. In addition to her teaching and research, she founded the Verband der akademischen Frauen Österreichs [Association of Austrian Woman Academics], which she was to chair until 1930. She published regularly and led the University of Vienna’s Institute of Phonetics from 1928, but she still faced constant resistance (even in academic circles) and had to fight for recognition. The anti-Semitic sanctions following Austria’s “annexation” by Nazi Germany ultimately put an end to Richter’s academic career. Her teaching license was revoked, and 1942 saw her deported together with her sister Helene to the ghetto of Theresienstadt, where both were to lose their lives. Today, we are reminded of Elise Richter’s life and achievements by a lecture hall at the University of Vienna that bears her name as well by as an award of the German Society of Romance Philology that is dedicated to her memory.

4. Käthe Leichter, sociologist and Social Democratic politician (1895–1942)

The contribution made by Käthe Leichter to the Social Democratic movement’s development in Austria cannot be overemphasised. Leichter’s political and journalistic dedication was broad in scope, manifesting itself officially and then underground right up to her arrest in late May of 1938. Having forced her admission to the study of political science at the University of Vienna with a lawsuit in 1914, Leichter took the final exams for her degree in Heidelberg. She went on to earn her doctorate with honours under Max Weber in 1918, whereupon she returned to Vienna and met her future husband, the journalist Otto Leichter. In Vienna, she joined the Social Democratic Workers’ Party, in which she served between 1919 and 1934 as deputy chair while also being responsible for educational work and women’s employment issues in the party’s Vienna district group. And in 1925, she was charged with setting up a women’s department at the Vienna Chamber of Labour. When her activities became illegal due to the repressions of the Dollfuss regime, Käthe and Otto Leichter secretly co-founded the “Revolutionary Socialists of Austria”. The Leichters’ political activities forced them to attempt escape to the USA in 1938, but only Käthe’s husband and two sons succeeded. Käthe Leichter remained behind, was arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo, and was transferred to the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp in 1940. Two years later, she died at the sanatorium and mental hospital in Bernburg/Saale as a victim of the National Socialists’ euthanasia programme.