For Humanity and Against War

Resistance in Dark Times

In the 1930s, women were still widely believed to be naïve, politically ignorant, and harmless—a fact that sometimes enabled them to achieve more than their male counterparts in the efforts to resist National Socialism. But if they did eventually fall into the hands of the Gestapo, there was no mercy: they suffered just as much torture, violence, and terror as did men. But even so, numerous women made a conscious decision in favour of humanity, against war, and for an independent Austria free from foreign occupation—a decision for which, if need be, they were prepared to give their lives.

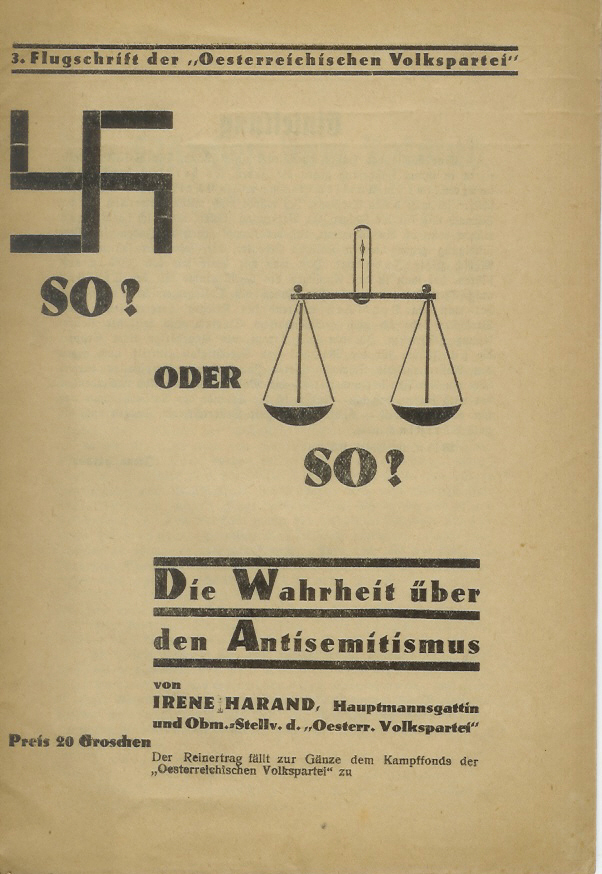

Irene Harand, World Movement against Racial Hate and Human Suffering, “Righteous among Nations” (1900–1975)

Even in the days of Austria’s First Republic, Irene Harand recognised the threat to segments of the Austrian populace due to rising anti-Semitism and the growth of the National Socialist movement. As a staunch critic of Germany’s Nazi regime, she co-founded the World Movement against Racial Hatred and Human Suffering in 1933, also known simply as the Harand Movement. In her 1935 book Sein Kampf – Antwort an Hitler (His struggle [an answer to Hitler]), published at her own expense and thereafter released in English and in French, she attempted to refute anti-Semitic beliefs. Following Germany’s takeover of Austria in 1938, a bounty was offered for Harand’s capture and her writings were publicly banned. Harand succeeded in emigrating to Great Britain and subsequently to the USA, where she became involved in numerous organisations for Austrian exiles. She was a co-founder of the Austrian Institute, which later became the Austrian Forum when post-war Austria set up its own official Austrian Cultural Institute. The Austrian Forum, which worked for the benefit of emigrated artists and authors, discontinued its operations in the early 1990s. But the memory of its activities lives on in the Austrian Cultural Institute’s present-day name: Austrian Cultural Forum. Harand herself is remembered in Vienna by the public housing complex Irene-Harand-Hof and the square Irene-Harand-Platz, and Yad Vashem honours her as “Righteous among the Nations”.

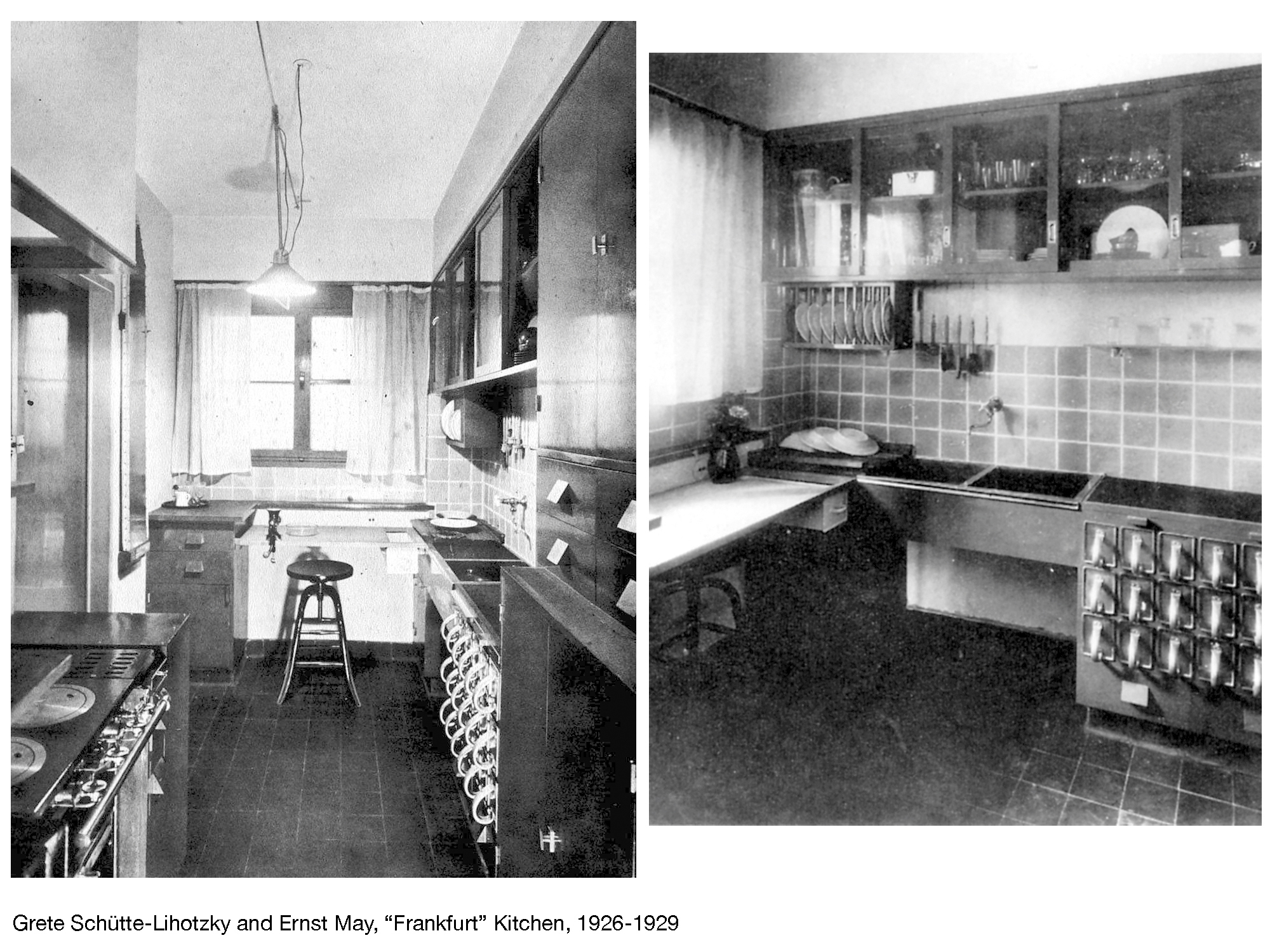

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, architect (1897–2000)

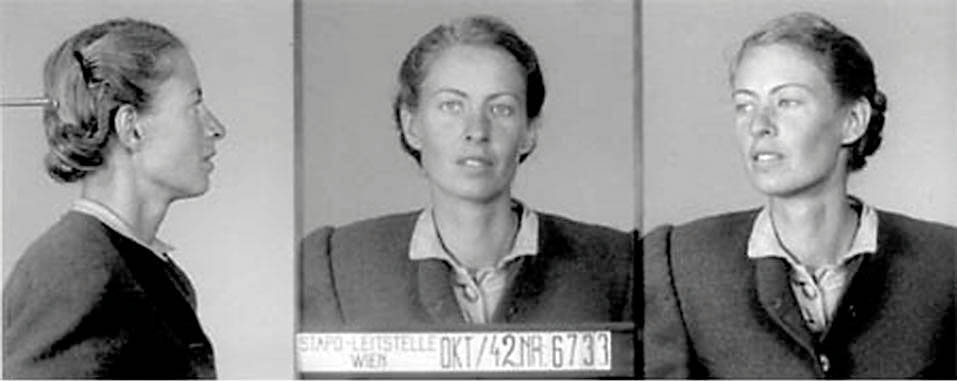

When Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky celebrated her 100th birthday in 1997, she said that nobody would have believed back in 1916 that a woman would ever be commissioned to design a building. But even so, her mother succeeded in persuading a friend of the family—none other than Gustav Klimt—to write a letter of recommendation for young Grete. She thus became the first woman to study architecture at the Imperial-Royal School of Arts and Crafts. She soon realised the increasing importance of functionality, working on a residential complex for disabled war veterans together with her mentor Adolf Loos following the First World War. And in 1926, she was called as an architect to Frankfurt, where she would design apartments for working women. Her “Frankfurt Kitchen”, which saved space and physical movement, was to become world-famous as the precursor to modern built-in kitchens. And together with her husband, the architect Wilhelm Schütte, whom she had married in 1927, she moved to the Soviet Union in 1930, where the two of them planned a city in the southern Urals. When their papers expired in 1937, they moved on to London, to Paris, and then to Istanbul, where they taught at the Academy of Fine Arts. Later on, in 1940, the communist architect Herbert Eichholzer, who was organising a resistance movement against the Nazi regime, travelled together with Schütte-Lihotzky to Vienna. They were discovered and arrested just a few weeks after arriving. Eichholzer was executed, while Schütte-Lihotzky was sent to a prison in Aichach, Bavaria. Following the war, official Austria boycotted the communist and former resistance fighter, for which reason she worked mainly in socialist countries. And it was only quite late that her work was publicly recognised by her homeland.

Sister Maria Restituta, resistance figure (1894–1943)

It was at the young age of 19 that the shoemaker’s daughter Helene Kafka became a Franciscan nun and assumed the name Maria Restituta. And following Austria’s annexation by Germany, the hospital of the “Franciscans of Christian Love” in Mödling—where she served as the surgery ward’s head nurse—was not spared from the influence of Nazi ideology.

But Sister Restituta refused to remove the crucifixes from the sickrooms. This, plus the fact that she had distributed flyers with a summons “to German Catholic youth” in the hospital, was to seal her fate. The physician Dr. Stöhr, a Nazi loyalist, denounced the pious, universally loved nurse, and she was arrested in the operating theatre on Ash Wednesday of 1942. The underlying political reason was that the National Socialist Party Chancellery sought to “break” the influence of the Christian churches “completely and finally” and wanted to make an example of her. Maria Restituta was decapitated on 30 May 1943. Until the very end, she had given courage and solace to her fellow prisoners. And in 1998, she was beatified by Pope John Paul II during his visit to Vienna.

Dorothea Neff, actress, “Righteous among the Nations” (1903–1986)

The career of Munich-born and -raised Dorothea Neff (*1903) took her to various German cities before she received a permanent position at Vienna’s Volkstheater in 1939. Though Neff was frequently cast as a classic heroine, she exhibited fearlessness and will to resist inhumanity above all in the private sphere. At the risk of her career and her own life, she hid her Jewish friend—costume designer Lilli Wolff—in her apartment, thus rescuing her from persecution by the National Socialist regime. Hunger, illness, and the constant fear of being discovered characterised these two women’s everyday life throughout this difficult period, during which Lilli also once used a false identity in order to undergo a necessary tumour operation in the hospital. While Wolff emigrated to the USA following the war, Neff remained in Vienna and went on to become the darling of the city’s post-war theatre scene. She continued her career at the Volkstheater, the Burgtheater, and the Akademietheater—and kept on performing even after going completely blind in 1967. Neff was recognised by Yad Vashem as “Righteous among the Nations” in 1979.

Ella Lingens, physician, “Righteous among the Nations” (1908–2002)

1948 saw the London release of a book entitled Prisoners of Fear, the memoires of the Viennese physician Ella Lingens. In it, Lingens described the inferno that was the Auschwitz Concentration Camp and portrayed the desperate efforts of the prison doctors there, who attempted to control raging epidemics with hardly any medicines available to them. Ella and her husband Kurt Lingens had offered help to their Jewish friends in Vienna following Austria’s takeover by Germany in 1938. They had hid valuables, taken a persecuted couple into their home, and organised hideouts. Plans to escape to Switzerland came to naught when they were betrayed by an informer. The Lingenses were thereupon separated from their three-year-old son and detained at Vienna’s Gestapo headquarters. Kurt Lingens was sent to an army penal unit in Russia, while Ella Lingens was transferred to Auschwitz in February of 1943. Although she had already heard rumours about the camp before arriving there, she had not believed them and was thus in no way prepared for what she would see there. “Even those who experienced it cannot wholly comprehend it,” wrote Ella Lingens at the conclusion of her concentration camp memoires. She and her husband were honoured by Yad Vashem as “Righteous among the Nations” in 1980.