Nicht nur Musen

Claiming an Active Role in Life and the Arts

For centuries, women were prevented from becoming fine artists. The official reason for this was that the arts academies used nude models to teach drawing, and that the sight of naked bodies was too much for women to handle. Thus it came that women’s role in art was often reduced to that of the muse. Behind every artist was a strong woman, it was said—and often enough, this was true. The realisation that women could themselves be great artists only gradually began seeping into the public consciousness.

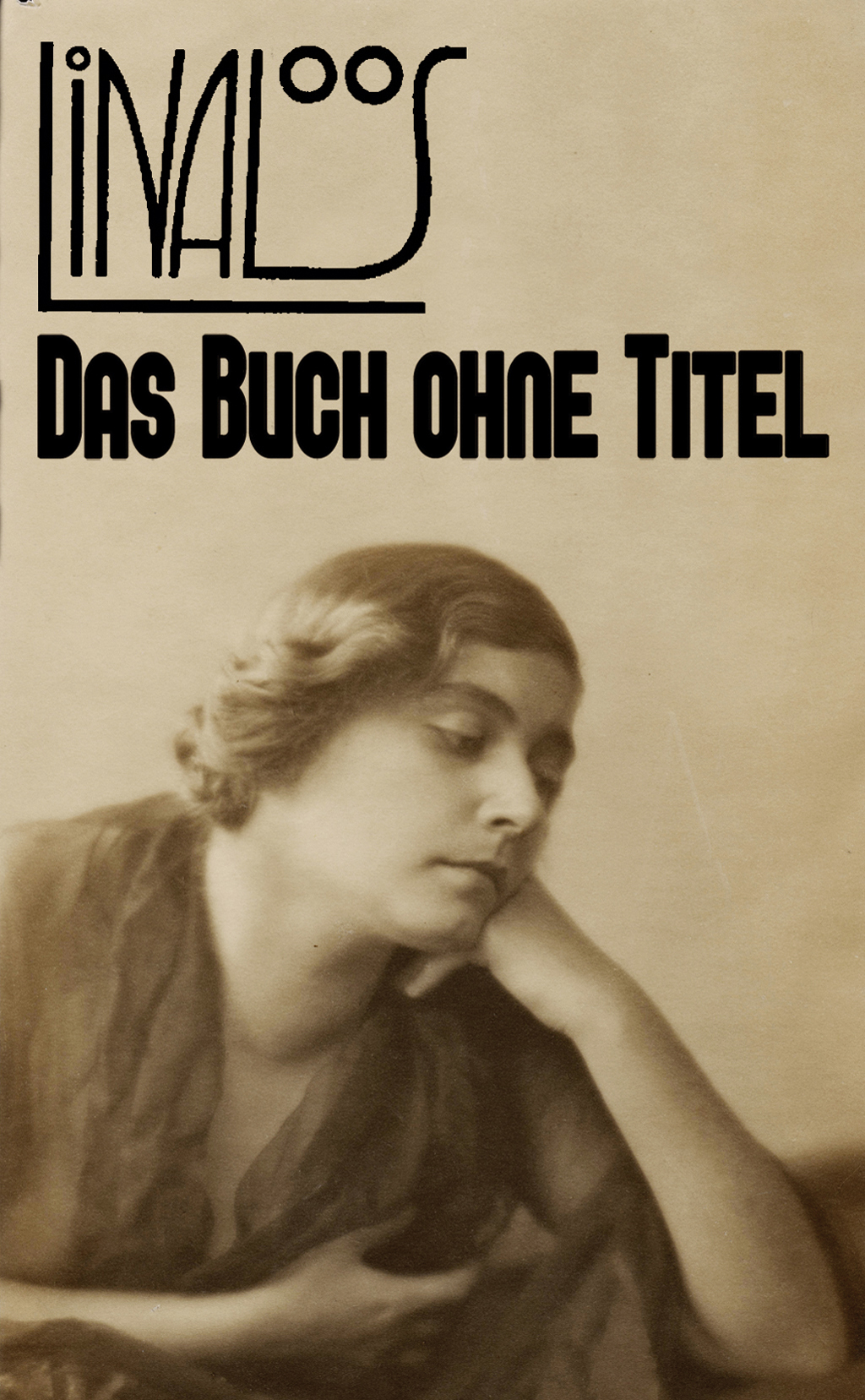

1. Lina Loos, actress, columnist (1882–1950)

Lina Loos was an actress, a comedienne, a columnist, a book author, and a politically active and universally respected figure of Vienna’s art scene and coffee house literati. She had trained as an actress at the Conservatory and at the Academy of Music. And between 1902 and 1905, she had also been married to a famous man: the architect Adolf Loos. But the secondary role of the muse was not enough for Lina Loos. In 1904, she began writing regular pieces for various newspapers and magazines, including the Neues Wiener Tagblatt. And though her acting career was not crowned by any spectacular roles, it did still take her to Berlin, to Munich, and—in the years following her divorce—even to St. Petersburg and the USA. Prior to the outbreak of the First World War she returned to Vienna, where she would grace the stages of theatres including the Raimundtheater and the Volkstheater until 1938. Thereafter, she was active mainly as a writer and became increasingly involved on the political level. She was vice-president of the Bund demokratischer Frauen [Federation of Democratic Women] and a member of the Österreichischer Friedensrat [Austrian Peace Council]. 1947 saw the release of her work Das Buch ohne Titel [The Book Without a Title], her first—and, during her lifetime, only—independent publication. She spent her adult life surrounded by a multitude of friends and admirers from the art and cultural worlds including Peter Altenberg, Egon Friedell, Franz Theodor Csokor, Arthur Schnitzler, Else Lasker-Schüler, and Berta Zuckerkandl.

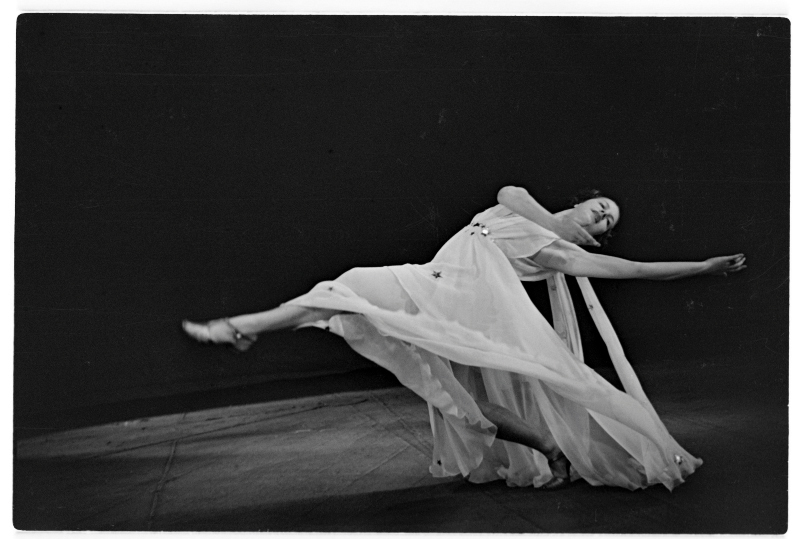

2. Grete Wiesenthal, dancer (1885–1970)

In dance circles, the name Wiesenthal is to this day unequivocally associated with both the dance group of the Wiesenthal Sisters and the “Wiesenthal Technique”—a style of dance based on the Viennese waltz rhythm that counters the static elements of classical ballet with particularly light and energetic turning motions. Grete Wiesenthal, like her sisters Elsa and Bertha, learned ballet in the classical manner at the ballet school of the Vienna Court Opera, where she began appearing as a solo dancer at the tender age of 17. Her talent attracted the attention of Gustav Mahler, who selected her for the title role in La muette de Portici (The Mute Girl of Portici). But despite her success with the Court Opera, 1908 saw her set out to work independently, making her extremely successful debut along with her two sisters at the cabaret Fledermaus—a performance followed by guest appearances in Berlin, St. Petersburg, Budapest, and Prague. Her collaboration with Max Reinhardt soon helped put her on course for a promising solo career, and 1913 saw her expand her repertoire by appearing in silent movies. Grete Wiesenthal went on to found and head her own ballet school, and she also taught from 1934 to 1951 at the Academy of Music and Performing Arts Vienna. Her apartment was regarded as one of Vienna’s last great salons, and it also became a refuge for regime opponents during the Third Reich.

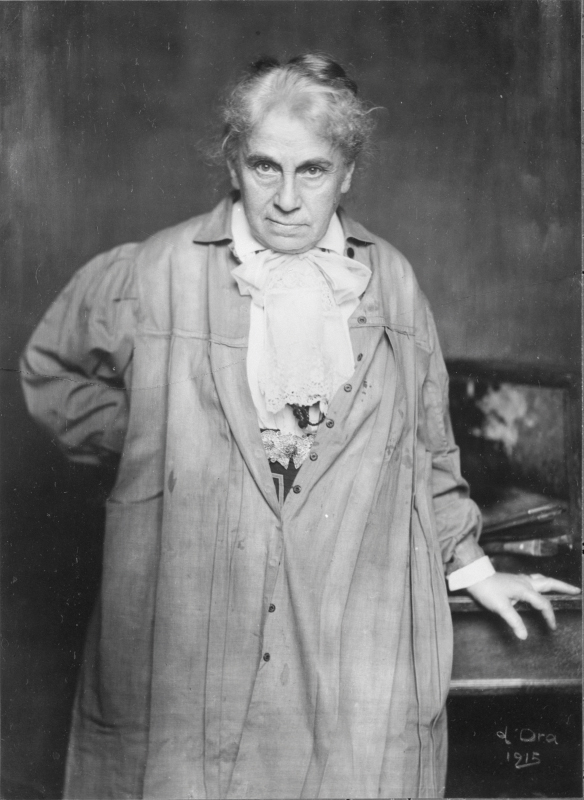

3. Tina Blau, painter (1845–1916)

The artistic ambitions of Tina Blau took root in fertile soil. Her father supported her from the very beginning, arranging private lessons with the Austrian painter August Schaeffer. Schaeffer recognised her love of nature and motivated her to focus on landscape painting. And landscapes were also a logical choice of speciality, since women were barred from learning to draw nudes and studying at the Academy.

1882 saw Blau participate in the First International Art Exhibition at Vienna’s Künstlerhaus, and her painting Spring in the Prater attracted considerable attention. Painter Hans Makart singled it out as the best of the entire show, and it was presented soon thereafter at the Salon de Paris, where it received a “mention honorable”. In 1883, Blau moved with her husband to Munich, where she taught landscape and still life painting at the Frauenakademie [Women’s Academy] there. And following her husband’s death, she engaged in extensive travel before ultimately returning to Vienna after ten years’ absence. There, she joined forces with figures including Rosa Mayreder to found the Kunstschule für Frauen und Mädchen [Art School for Women and Girls], which she was to head for the next two decades.

4. Hedy Lamarr, actress and inventor (1914–2000)

In the 1930s, Hedy Lamarr—famed for cinema’s first-ever nude scene—was considered the world’s most beautiful woman. The Vienna native parlayed her international fame into a Hollywood career that saw her act in around 30 movies for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Nobody knew, however, that she spent her free time developing a secure wireless technology that now forms the basis of US satellite defences and mobile telephony. This invention was so ingenious that film producers forbade her to speak of it: ingenuity was not viewed as a desirable quality in a film diva, whose job was apparently limited to being pretty. In the late 1950s, Hedy Lamarr—by then a mother to three children—withdrew from the film business. But towards the end of her life, her achievements as both an actress and an inventor were recognised in the form of multiple honours in both the USA and Austria. She never again appeared in public, though, instead sending her son to accept her honours.

5. Alma Mahler-Werfel, composer and salonnière (1870–1964)

Alma Mahler-Werfel was born into an artistic world that she was soon to actively help shape. The first among the many men who fell for her was most likely Gustav Klimt. But in 1902, she married the composer and Court Opera Director Gustav Mahler, who was 20 years her senior. Mahler suppressed the abilities of his wife, who was a highly gifted composer, saying to her: “How exactly do you imagine such a composing couple being? (…) From now on, you have only one job: to make me happy.” Although the marriage grew increasingly difficult, Alma Mahler dedicated her life to her ailing husband. But when he passed away in 1911, she quickly assumed the role of the desirable widow and began an affair with the young painter Oskar Kokoschka. Alma eventually wed the architect Walter Gropius, since she was expecting a child with him—but she divorced him two years later to marry the author Franz Werfel in 1917. Werfel, like Gustav Mahler, was a Jew, and although Alma Mahler-Werfel repeatedly exhibited anti-Semitic tendencies, she supportively followed Werfel into American exile. Before she passed away in New York, in 1964, she ensured that she would be remembered by posterity with her autobiography My Life, My Loves, in which she portrayed herself as the twentieth century’s most desired woman.