Towards the Public and Political

Women’s Movements ca. 1900

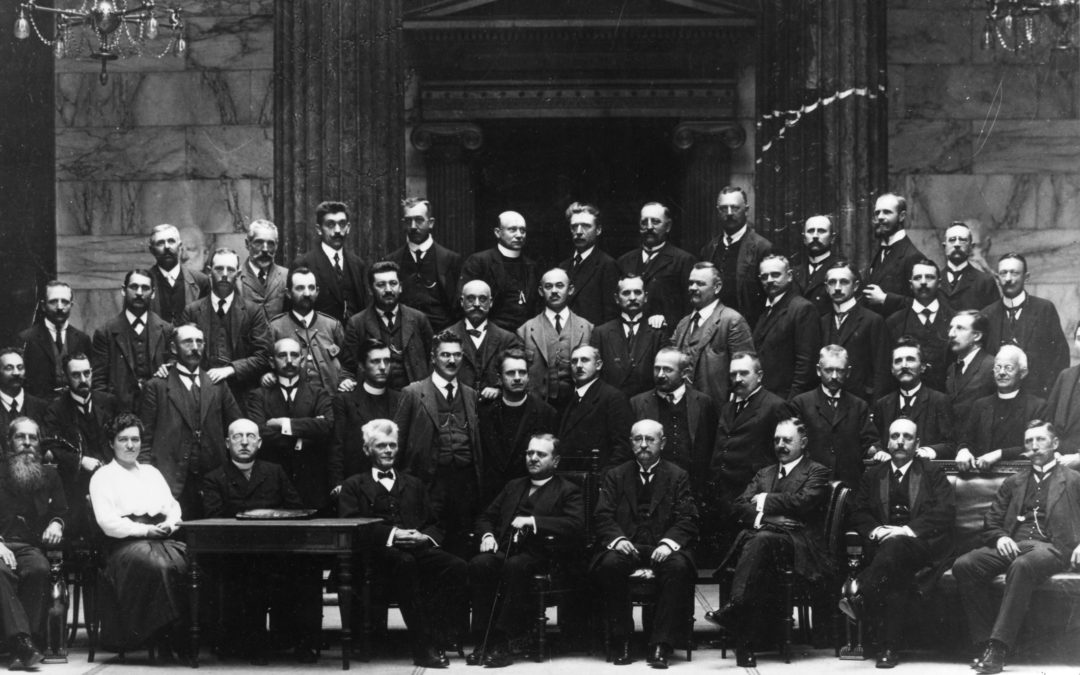

Up to the beginning of the 20th century, women were excluded from the public political sphere. They were allowed neither to be members of political organisations nor to take part in political gatherings. But despite such legal bans, women repeatedly found opportunities and forms via which to make their voices heard. They founded their own organisations and were so persistent in challenging sex-based limits that, by the beginning of the 20th century, they were able to harvest the first fruits of their arduous struggle.

Marianne Hainisch, women’s movement founder (1839–1936)

It was the economic repercussions of the American Civil War that moved Marianne Hainisch, wife of an industrialist and mother of two, to become a campaigner for women’s rights. A friend’s husband had been driven into bankruptcy due to the American cotton crisis and subsequently fallen seriously ill. The resulting situation revealed the relative uselessness of the genteel sort of education typically enjoyed by upper-class daughters if the point was to feed a family. “At that point, it suddenly dawned on me that bourgeois girls needed to be prepared to accept gainful employment,” wrote Hainisch. “I was deeply moved and became a fighter for women’s advancement that very day.” On 12 March 1870, at the Viennese Women’s Employment Association, Hainisch introduced a motion concerning “the issue of women’s education” and was from that point onward to campaign unfalteringly for equal rights in education. And when Auguste Fickert, Rosa Mayreder, and Marie Lang founded the General Austrian Women’s Association in 1893, she began working together closely with these three despite receiving no support from the state. After all, the employment of private means had made it possible to finally open Austria’s first girls’ Gymnasium, or academic secondary school, in 1892. Ten years later, in 1902, Hainisch united the most important women’s organisations to form the League of Austrian Women’s Associations; she also fought tirelessly for women’s right to vote and succeeded her friend—the Nobel Peace Prize winner Bertha von Suttner—as chairwoman of the league’s Peace Commission. After the First World War, in 1919, she did finally get to experience the enactment of women’s suffrage. One year later, her son became the Republic of Austria’s first federal president. And in 1929, at the advanced age of 90, she founded the Österreichische Frauenpartei [Austrian Women’s Party]. But despite all her progressive ideas, this bourgeois women’s liberation advocate never abandoned the ideals of marriage, motherhood, and family. Hainisch, a pioneer of the women’s movement, died in Vienna in 1936 shortly before what would have been her 97th birthday.

Auguste Fickert

Teacher, women’s rights advocate, social reformer (1855–1910)

Fifteen years after Auguste Fickert’s death, a committee of women formed with the intent to erect a monument in her memory. They succeeded, and today, she stands carved in marble as the only non-royal woman at Vienna’s Türkenschanzpark. Its plinth bears the words: “Full of courage and spirit, she devoted her life to high ideals.” This she did so uncompromisingly and exclusively that she was left with no time at all for a private life. In her obituary, Rosa Mayreder praised her comrade’s “self-sacrificing devotion” and “glowing conviction”. And it was probably such energy that also made her that member of her generation who accomplished the most for Austria’s women. Alongside her activities as a teacher, she constantly worked to further her own education and bring together an international network. And since she realised that most women would only adopt an emancipatory consciousness if they were shaken up and educated, an important point was women’s right to study at university, which she was ultimately able to realise. But her other central demand, “equal pay for equal work”, is something that still has yet to be fully achieved.

Hildegard Burian, social policy-maker and founder of Caritas Socialis (1883–1933)

Many of the Austrian state’s social achievements that seem a matter of course to us today were made possible in the first place by the dedication and initiative of people like Hildegard Burian. She grew up as Hildegard Freund in Berlin and in Zurich, where she was one of the first women to study German philology. Following her marriage to the Hungarian Alexander Burian, she moved to Vienna, where she began working to ameliorate the precarious situations with which she saw working-class families confronted. At first, she concentrated above all on combating child labour. But women’s rights were also a major concern of hers. 1912 saw her found the Verein christlicher Heimarbeiterinnen [Association of Christian Women Home Workers] and thereafter, in 1918, she brought all the women’s labour unions into the association Soziale Hilfe [Social Assistance]. Her declared goals were the introduction of a minimum wage, legal protections and financial support in cases of illness, and a right to assistance in childbirth. “Full interest in politics is part of practical Christianity,” was her conviction. And in keeping with this statement, she was also a politician between 1918 and 1920. After being called to serve in Vienna’s City Council, she was elected in 1919 as the first female Christian Social Party member of Austria’s new National Council. And on 4 October of the same year, with help from Federal Chancellor Dr. Ignaz Seipel, she founded Caritas Socialis, a congregation of sisters that to this day works on a non-profit basis to help the ill, the socially disadvantaged, and those in need of nursing care.

Irma von Troll-Borostyáni, author and women’s rights activist (1847–1912)

Immediately following Irma von Troll-Borostyáni’s death, obituaries appeared in the most important German-language dailies. The Social Democratic paper Salzburger Wacht praised her as one of “the best and most noble of her line, and a herald of women’s emancipation whose name is known far beyond the borders of Austria.” In the magazine Neues Frauenleben [New Women’s Life], Rosa Mayreder wrote her words “at the grave of a woman who has made lasting contributions to the Austrian women’s movement, and who—through her numerous writings—contributed much to spreading and realising the idea of the women’s movement. Austria can feel honoured that Irma von Troll-Borostyani was among the first women whose achievements as an author forced the broader public to take women’s problems seriously.” The works of the author thus honoured were not bestsellers, but their effects still cannot be underestimated. Her major study on women’s issues, Die Mission unseres Jahrhunderts [The Mission of our Century] of 1878, was still written in an era where any thought of emancipation was interpreted as a pathological aberration. But her unyielding nature sustained her spirited campaigning and writing. She thus became Austria’s first woman to dare address the problem of prostitution, as well as the first to explicitly demand “equality of the sexes”. And interestingly enough, her combative polemics in support of social change called on both women and men to do their parts.