“My Plan: To Arrive!”

Women Authors

From the second half of the twentieth century, Austrian women became more and more visible in public discourse. This is perhaps most clearly recognisable in the sudden concentration of world-famous female authors, who rose to become the most important literary voices of the German-speaking world.

Ingeborg Bachmann, author (1926–1973)

Klagenfurt native Ingeborg Bachmann considered the day Hitler’s troops marched into Austria to have been the day her childhood ended. But it was in autumn 1946 that Bachmann went to Vienna to study philosophy, German philology, and psychology. As early as her Klagenfurt days, she had published her first story—Die Fähre (The Ferry)—in the regional newspaper Kärntner Illustrierte. Vienna now provided her with the opportunity to publish initial poems and become part of the literary circle associated with Hans Weigel. It was there that she also met Paul Celan, a formative influence on her subsequent writing. Bachmann earned her doctorate in 1950 with a dissertation on the reception of Martin Heidegger, and following several trips abroad, she went to work as a journalist for the “Rot/Weiß/Rot” group of radio stations. In 1952, she made waves when she attended her first meeting of the literary association Gruppe 47. And following the publication of her first poetry collection, Die gestundete Zeit [Deferred Time] (1954), she moved to Italy to live as a freelance author. For her poetry and prose, Ingeborg Bachmann received numerous awards, including the Gruppe 47 Prize (1953), the Georg Büchner Prize (1964), and the Grand Austrian State Prize for Literature (1968). What’s more, her novel Malina (1971)—generally viewed as a coming-to-terms with her relationship with Max Frisch—became an international bestseller. Bachmann’s life ended tragically in 1973 when a fire in her Rome apartment left her with serious burn injuries, to which she succumbed nearly three weeks later.

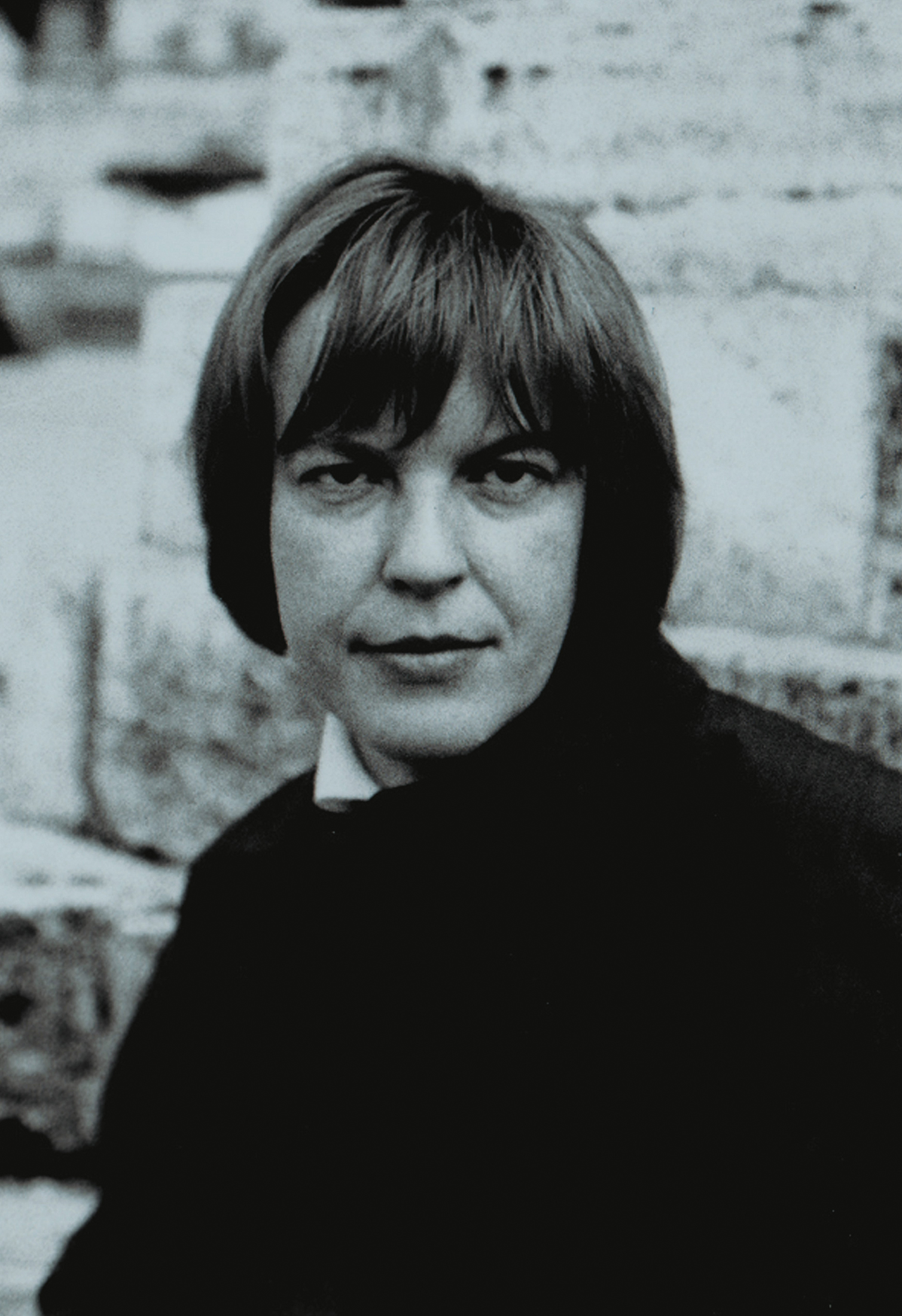

Ilse Aichinger, author (1921-2016)

“You don’t survive everything that you survive,” reads a sentence by Ilse Aichinger. As a half-Jewish child, she had been a target of the Nazis’ anti-Semitic persecution. Her twin sister succeeded in fleeing to Great Britain in 1939 thanks to the children’s rescue effort known as the Kindertransporte, while Ilse stayed behind in Vienna with her mother. But they escaped the pogroms that ensued—in contrast to Ilse’s grandmother, aunts, and uncles, who were deported to Minsk and murdered there. Following the war’s conclusion, Aichinger began studying medicine but soon dropped out in order to write her autobiographical novel Die größere Hoffnung [Herod’s Children] (1948). During her studies, she had already published numerous essays—including “Das vierte Tor” [The Fourth Gate], which was the first work of Austrian literature to make a theme of concentration and extermination camps. The awarding of the Gruppe 47 Prize to her short story “Spiegelgeschichte” [Mirror Story] made her known to a broader readership and bolstered Aichinger’s increasing ability to make a living from work as a writer. Furthermore, attending the Gruppe 47 meeting acquainted her with authors such as Ingeborg Bachmann, Paul Celan, Thomas Bernhard, and especially Günter Eich, whom she married in 1953. Following the deaths of her husband and her mother, Ilse Aichinger went to Frankfurt at the invitation of publisher Fischer-Verlag, but she returned to Vienna in 1988. Her literary oeuvre encompasses one novel, stories, and short prose works, as well as radio plays and contributions to the Austrian daily Der Standard. Aichinger was awarded the Grand Austrian State Prize for Literature in 1995.

Marlen Haushofer, author (1920–1970)

Die Wand (The Wall) (1963), Marlen Haushofer’s third and most successful novel, portrays the fate of a woman who is cut off from civilisation in the midst of a mountain wilderness surrounded by an insurmountable wall. Loneliness, social confinement, and the bourgeois family and role models that circumscribed women’s lives were themes that characterised many of Marlen Haushofer’s works. Following a failed relationship with the father of her first child, 1940 saw her become acquainted with the medical student Manfred Haushofer, with whom she then had a son. In Vienna, she studied German philology and art history but stopped working on her dissertation and began publishing her initial stories. Her husband’s job then entailed a move to the town of Steyr in 1947. But Marlene Haushofer continued seeking contact to Austria’s literary scene, first belonging to the circle of Hermann Hakel (publisher of the literary periodical Lynkeus) and then to that of Hans Weigel, which met at Café Raimund.

At Weigel’s advice, Haushofer refrained from publishing her first two novels and instead first published the story “Das fünfte Jahr” [The Fifth Year] in 1952, for which the Austrian state awarded her its Outstanding Artist Award for Literature. Between 1955 and 1957, Zsolnay Verlag published her novels Eine Handvoll Leben [A Handful of Life] and Die Tapetentür [The Concealed Door]. Both texts deal with the difficult attempt to emancipate oneself as a woman. Haushofer’s private life was beset by crises, and 1958 saw publication of the novella Wir töten Stella [We Murder Stella], in which family was presented as something existentially destructive. In a similar vein, her final novel, Die Mansarde (The Attic) (1969) portrays the deceptive idyll of a bourgeois marriage maintained only to keep up appearances. In 1970, Marlen Haushofer died of bone cancer in a Viennese hospital.

Christine Lavant, author (1915–1973)

In 1915, Christine Lavant was born in Carinthia’s Lavant Valley to the disabled miner Georg Thonhauser and the mending tailor Anna as the youngest of their nine children. She took her home valley’s name as her pseudonym. As a child, Christine—physically weak and afflicted by lung ailments—had been a social outsider. But early on, she discovered literature and began writing herself. At the age of 24, following her parents’ deaths, Christine married the significantly older painter Josef Habernig. The couple lived an isolated and financially precarious life. Lavant’s trademark rural kerchief, her hollow cheeks and protruding eyes, her thin and hunched body, and her fascination with religious, mythical, and philosophical literature all contributed their part to her image as a “poetry-writing herbwife”. But many important Austrian literary figures expressed their sincere esteem for her poetry. Beginning in 1948, Victor Kubzak’s renowned publishing house Brentano-Verlag in Stuttgart began publishing her texts, including her story Das Kind [The Child] (1948), the poetry volume Die unvollendete Liebe [The Incomplete Love] (1949), and Die Bettlerschale. Gedichte [The Beggar’s Bowl. Poems] (1956). Christine Lavant’s final years witnessed a back-and-forth between hospital stays and artistic success. And in 1970, three years before her death, Lavant was awarded the Grand Austrian State Prize for Literature.

Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach, author (1830–1916)

Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach was born in 1830 as Baroness Dubský at Zdislavice Castle near the Moravian town of Kremsier (today’s Kromĕřiž). Her parents—from an old Austrian family on her father’s side and a North German Protestant family on her mother’s—nurtured her enthusiasm for learning and her great interest in literature, philosophy, and theatre from a young age. But even so, they held her pursuit of a career as an author to be “something wrong and sinful”, as Marie would remember in her autobiography Meine Kinderjahre [My Childhood Years]. In 1848, at the age of 18, she married her cousin Moritz von Ebner-Eschenbach, who at first taught physics and chemistry as a professor at the Military Engineers’ Academy in Znaim (today’s Znojmo). In 1856, the childless couple moved to Vienna. There, Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach focused above all on writing, especially on the authoring of plays. She was to enjoy no success as a dramatist, with the lion’s share of her stage works going unperformed. Instead, she achieved her breakthrough in precisely that literary genre that she herself had called “the most humble form” of literature: the story. Her short novel Božena (1876), as well as Die Geschichte einer Magd [The Story of a Maid] (1876), Aphorismen (Aphorisms) (1880), Dorf- und Schlossgeschichten [Village and Castle Stories] (1883) including Ebner-Eschenbach’s most famous novella Krambambuli (Krambambuli: The Story of a Dog), and her novel Das Gemeindekind (Their Pavel) (1887) cemented her stories’ status as part of the Austrian literary canon. Ebner-Eschenbach’s well-heeled aristocratic upbringing did nothing to diminish her concern for “the little people”. Her works, in the spirit of Austria’s late Enlightenment, portray above all the fate of society’s outsiders and members of the lower class. In 1899, she became the first woman to receive the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art.